Chapter III: Fostering a New Interdisciplinary Approach to Problems of Brain and Behavior, 1970-1974

In the early 1970s, the nascent Society set up an office with NAS support and concentrated on fostering a new interdisciplinary approach to brain and behavior research. This was an exciting period for the field, with such developments as the isolation of the opioid receptors in the brain, which heightened public interest in “natural highs” and solutions to the problems of pain and addiction; the fields of learning and memory enhanced by Tim Bliss and Terje Lomo’s description of long-term potentiation and Eric Kandel’s findings that habituation and sensitization altered the strength of synaptic connections, which enhanced the fields of learning and memory; and the introduction of CT, MRI, and PET scanners which made the interior of the brain visible during behavior.

The newly christened field had the opportunity to capitalize on these findings to build support and funding for such interdisciplinary work and for the ideal of a diverse but collaborative and self-governing, enterprise.

The major issues confronting the Society at this time were: 1) to promote scientific communication and collaboration; 2) to ensure and perpetuate interdisciplinary representation in membership and governance; 3) to promote public interest and understanding through informational programs and the creation of a logo. The Society organized around its Annual Meetings in the fall, where members presented and discussed their work and extended their professional and scientific networks. The Annual Meeting was also the Society’s major expenditure and source of income. The Council met two or three times each year to plan the Annual Meetings and to consider questions of membership and finance; the quarterly Neuroscience Newsletter acted as the adhesive cementing long-distance and transdisciplinary ties in between the yearly gatherings.

In setting membership rules and leadership criteria, the early leaders of SfN shaped the Society in ways that reaffirmed their definition of an expansive neuroscience that explicitly addressed questions across multiple domains. They declared membership open to any scientist in North America who demonstrated “serious interest in research evidenced by publication” and “a sincere interest in an interdisciplinary approach to problems of brain and behavior.” To facilitate the approval process, members could sponsor their colleagues and students41 and dues were set low at $15 per year, and $3 for students.42 This strategy proved immediately successful. By December 1969, 6 months after the founding, 500 individuals, representing disciplines ranging from biochemistry to clinical psychology, had joined the Society and formed 6 local chapters. Each subsequent Council meeting brought the approval of new chapters, which continued to form all over the country. By the time the Society met for its first Annual Meeting in October 1971, there were 25 approved chapters in 18 states, as well as 2 in Canada.43 The chapters often met monthly to share results and techniques and to engage in interdisciplinary seminars.

Although SfN began under the aegis of U.S. scientific leadership at the NAS, the founders recognized the importance of building a scientific community that extended beyond the borders of the United States. They were particularly keen on embracing Canadian and Mexican neuroscientists. Neuroscience was well established in Canada, where the Montreal Neurological Institute was a pioneering leader in the nascent field, and emerging as a field in Mexico, which was developing its own school of integrative neurobiology.44

Even more than geographic diversity, the Council valued intellectual diversity, especially if neuroscientists were to grapple successfully with the most compelling questions of the relationships between brain, behavior, and mind. To this end, the Council worked from the beginning to ensure that the leadership reflected a field that spanned the biological and behavioral disciplines.

Developing this breadth of leadership was not necessarily an easy task. At one point in March 1972 Louise Marshall noted a “danger … that the more self-aware, selfassured disciplines may run away with the Society. For example, with the […1971] election, the Council has a preponderance of neurophysiologists.” Therefore, the Council amended the bylaws that year so that officers would only serve one-year terms instead of two. Marshall and others expressed concerns about changing the bylaws so soon, fearing that the Council and Society would be in constant flux due to idealistic whims, but these fears proved unfounded.45

The SfN leadership maintained its commitment to supporting an interdisciplinary milieu. The Membership Committee again expressed diversity concerns in 1975, when it noted the minority of clinical researchers among members and requested advice from the Research Society of Neurosurgeons and the International Neuropsychologists Society on how to attract more members whose “primary identification may not be as neuroscientists,” but who nevertheless would find interdisciplinary collaborations useful and productive.46

The first elected Council was chosen from a slate “with careful consideration given to geographic and disciplinary distribution of candidates.”47 With 57% of the new Society voting, members chose neurophysiologist Vernon Mountcastle of Johns Hopkins as the first elected president, Neal Miller of Rockefeller University as the president-elect, and Mountcastle’s biophysicist colleague Martin Larrabee as secretary-treasurer.

The eight Council members included biophysicists, neurophysiologists, neuroanatomists, and an experimental psychologist, representing a diverse array of institutions, including NIH, Albert Einstein Medical School of Yeshiva University, Indiana University, the University of Rochester, and the University of California, San Diego.48 The first Council gathered in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on April 15, 1970, and began organizing its workload by creating committees on membership and chapters, the Annual Meeting, affiliations, and budget and finance (See Tables 4 and 5).

| The First Council Members |

|---|

| Wilfrid Rall (biophysics, NIH) |

| Theodore Bullock (neurophysiology and electroreception, UCSD) |

| William Neff (experimental psychology, Indiana) |

| Dominick Purpura (medicine and neuroanatomy, Albert Einstein and Yeshiva University) |

| Edward Evarts (neurophysiology, NIMH) Lawrence Kruger (neuroanatomy, UCLA) |

| Sidney Ochs (neurophysiology, Indiana) Robert Doty (neurophysiology, Rochester) |

The first elected Council gathered in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on April 15, 1970, and began organizing its workload by creating committees on membership and chapters, the annual meeting, affiliations, and budget and finance. (See Tables 4 and 5)

SfN Standing Committees 1970-1995

| Committee | Date established |

|---|---|

| Membership | 1970 |

| Chapters | 1970 (Changed to Chapters and Communication 1991) |

| Annual Meeting/Program | 1970 |

| Nominations | 1970 |

| Budget and Finance | 1970 |

| Affiliations | 1970 |

| Education | 1971 |

| Communications | 1972-1980 |

| Publications | 1972 |

| Social Issues | 1973 |

| Public Information | 1974 |

| Resolutions | 1978 |

| Minority Education, Training and Professional Advancement | 1985 (Subcommittee of Social Issues 1979-1984) |

| Governmental and Public Affairs | 1980 (Ad hoc Committee on Research Resources 1977-79) |

| Animal Research | 1985 (Ad hoc 1981) |

| Neuroscience Literacy | 1991 (Ad Hoc Committee on Secondary Education 1990) |

| Development of Women’s Careers in Neuroscience | 1998 (Ad hoc 1991) |

| History of Neuroscience | 1994 (Ad hoc 1992) |

SfN Ad Hoc Committees

| Availability of Primates | 1975-8 |

| Advisory Committee on the Boston Museum of Science Brain Exhibit | 1975-82 |

| Quality of the Annual Meeting | 1981-85 |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | 1981 |

| Student Services | 1987 |

| Public Education | 1988 |

| Decade of the Brain | 1990-99 |

The Council, in appreciation for their contributions to the establishment of SfN, named Ralph Gerard honorary president for two years and Louise Marshall special consultant to the Council, “until such time that it is determined by her or a future Council that the need for consultation no longer exists.”49

Marshall was instrumental in maintaining the connection between the new Society and the NAS-NRC’s Committee on Brain Sciences through this transition period. She described “the current relationship” at this juncture in these terms: “the umbilical cord has been cut but the infant not yet weaned.”50 With crisp prose peppered with her characteristic acerbic wit, she also edited and wrote most of the articles for the Neuroscience Newsletter from 1970 until 1977 (Figure 11), providing the single most extensive chronicle of SfN’s early struggles and aspirations.

The first issues of the Newsletter underscore the Society’s preoccupation with a democratic science, one that embraces multiple perspectives and that eschews elitism. Declaring the Newsletter the “conservator of the founding spirit of the Society,” Marshall wrote that the Society would shape the field by “its pluralism of disciplines connecting to form new insights, and its freedom from elitism,” and promised that “No one meeting, workshop, or publication (excepting the Society’s own) would be featured without equal space to others”51 in the publication’s pages. Her editorial introducing the goals and scope of the Newsletter concluded, “As a healthy organism, the Newsletter aims to survive through its capacity to perceive and respond to the environment, which in turn depends on the quality of the feedback it receives. This first issue, for which the Editor takes full responsibility, should serve as a stimulant.”52

Imagining Neuroscience

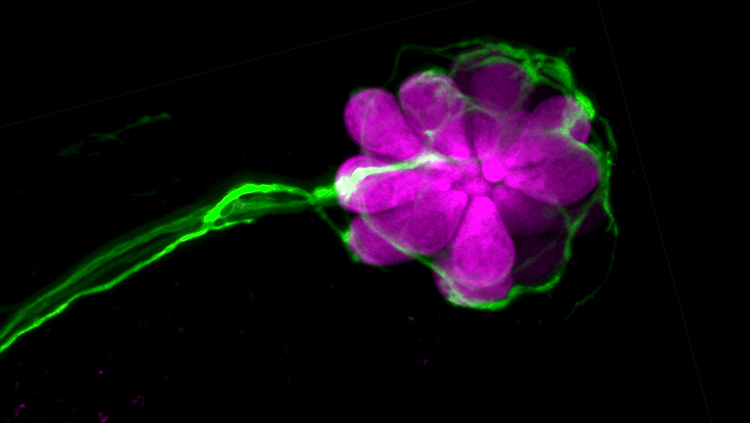

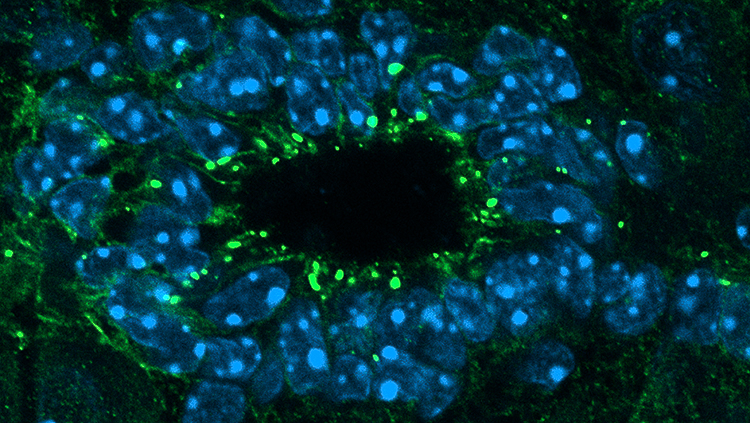

The effort to find a suitable logo illustrates the Society’s determination to forge an identity that ignored traditional disciplinary boundaries and gave a clear visual meaning as to what “neuroscience” meant as a field and as an endeavor. Each early issue of the Neuroscience Newsletter featured a different logo for the Society, submitted by scientists or graphic artists in anticipation of the 1972 Annual Meeting when members would be asked to vote on their favorite submission. The first logo to appear in the Newsletter, submitted by graphic designer Percy Martin, featured an eye in the center with neurons radiating outward, circumscribed by what appears to be a petri dish. (Figure 12) The second design, created by Julian Maack, an artist at the University of Utah, with input from Ed Perl, was a silhouette of a human head, with nerve cells and EEG readouts flowing out of the brain (Figure 12). The third option, designed by artist Timothy Volk for a neurobiology conference at the University of Wisconsin, graphically depicts some of the laboratory tools neuroscientists could use in their experiments, including DNA, primates, chemicals, EEG recordings, and video tapes (Figure 13).

A fourth logo, from June 1971, dispensed with scientific imagery, but proposed a graphic of “Neuroscience” and “Newsletter” (Figure 14) that “refers to the normal and the skewed distributions (natural, behavioral, statistical) basic to all work of neuroscience.”53 Other options featured representations of the brain, neurofiber bundles, and an EEG readout forming the N in Neuroscience (Figure 14).

The winning logo (Figure 15), submitted by Vernon Rowland of Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine reaffirmed the leadership’s vision of neuroscience as a synthetic scientific field.

And, as the most abstract of the submissions, it was a safe choice, while still privileging the brain over other sites of neuroscientific investigation. However, this was far from Rowland’s intention. He explained his logo (Figure 16) as follows: “The brain of a neuroscientist, in trying to encompass some other brain, must fragment it (analysis). The brains of neuroscientists form a Society for Neuroscience in order to put it back together (synthesis).”54 This compelling image appeared on Society publications from 1972 until November 1983.55 The logo’s multiple perspectives cleverly reflected the duality of the researcher as both the observing and observed brain.

A Society Realized

The Society held its first Annual Meeting in October 1971 in Washington, D.C., with a structure that changed little over the next two decades. Symposia, lectures, poster sessions, and public outreach gave reality to the Council’s efforts to create a vibrant community, enhanced by an intimate setting; all activities took place at the Shoreham Hotel.

Innovations included three simultaneous morning paper presentation sessions; the social program featured a performance of “Candide” at the Kennedy Center.56 The Planning Committee, chaired by Henry Wagner of the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS),57 included an educational program discussing the brain, consciousness, and the control of behavior. The program was directed at students, but open to the public, “to involve scientists, laymen, and students in a discussion of…brain in behavior that is open to the temper of the times.”58 The public session was the first in a series of Annual Meeting events designed to introduce the public and interested students to “information on and about the broad range of the neurosciences,” what neuroscientists studied, what they learned, and how their findings could benefit society.”59

The reactions of the 1,395 scientists (including 390 students) who attended this first meeting were overwhelmingly positive. Louise Marshall noted that many were “pleasantly surprised neuroscientists – surprised to see so many others from contingent disciplines with mutual interests, and surprised at the high quality of the sessions.”60 Planning Committee member Maxwell Cowan, a neurobiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, expressed relief that “many of the problems which I and others had foreseen just did not materialize.” He noted that the morning sessions were seen as “the most successful innovation in the program. …The only criticism of these sessions was that in some cases the material dealt with got lost in experimental detail.”61

SfN Annual Meeting Locations 1971-95

| 1971 | Washington, DC | |

| 1972 | Houston, Texas | |

| 1973 | San Diego, California | Video: Third Annual Meeting |

| 1974 | St. Louis, Missouri | |

| 1975 | New York, New York | Video: Fifth Annual Meeting |

| 1976 | Toronto, Canada | Video: Sixth Annual Meeting |

| 1977 | Anaheim, California | |

| 1978 | St. Louis, Missouri | Video: Eighth Annual Meeting |

| 1979 | Atlanta, Georgia | |

| 1980 | Cincinnati, Ohio | |

| 1981 | Los Angeles, California | |

| 1982 | Minneapolis, Minnesota | |

| 1983 | Boston, Massachusetts | Video: First Social Issues Roundtable |

| 1984 | Anaheim, California | |

| 1985 | Dallas, Texas | |

| 1986 | Washington, DC | |

| 1987 | New Orleans, Louisiana | |

| 1988 | 1988 Toronto, Canada | |

| 1989 | 1989 Phoenix, Arizona | |

| 1990 | St. Louis, Missouri | |

| 1991 | New Orleans, Louisiana | |

| 1992 | Anaheim, California | |

| 1993 | Washington, DC | |

| 1994 | Miami Beach, Florida | |

| 1995 | San Diego, California |

The table above lists the sites of the annual meetings through 1995.

Table 6 lists the sites of the Annual Meetings through 1995. Although all but two Meetings were held in the U.S., the leadership encouraged attendance from throughout North America and tried to select the locations most accessible to international members. In 1976, the Annual Meeting was held in Toronto and featured a special symposium, “Prospects in Neuroscience: A View From Three Nations.”62 The first president from outside the U.S., Albert Aguayo, an Argentinian-Canadian working at McGill, took office in 1987.

Annual Meeting attendance certainly is one core measure of success. From this perspective, SfN was spectacularly successful. As shown in Figure 18, Annual Meeting attendance during the 1970s rose far more rapidly than any of SfN’s founders could have imagined. A respectable number of 1,400 individuals had attended the 1971 Meeting. By the end of that decade, attendance had increased to almost 6,000, and abstract submissions (figure 19) were about to exceed 3,600.

But this was only the start. By the early 1990s, Meeting attendance had increased by 300–400%, to 18–22,000 annually, while abstract submissions kept pace, totaling 12,422 by 1995.88

Annual Meeting Highlights

The 1972 Meeting was scheduled for Houston and again included a public session on “Neuroscience in the Public Interest.” Although Floyd Bloom and other Society leaders saw the meeting as a valuable resource for neuroscientists across the country, they were concerned that members might be unwilling to make transcontinental journeys every year.63 Under the direction of F. G. Worden, the Houston Program Committee experimented with different types of presentations such as demonstrations, panel discussions of pre-circulated materials, and poster sessions, since “the launching of a new society offers an opportunity to try to rescue the scientific community from the straitjacket of the traditional format.”64 The majority of the proposed abstracts, however, were for the traditional 10-minute presentation format, so the Program Committee adjusted the schedule so as to accommodate both traditional and more “experimental” formats.65 The Committee planned nearly a full day of physiological and behavioral demonstrations and arranged for a “Women’s Hospitality Room” at the Shamrock Hotel where “social registrants” could relax and socialize during the day while their spouses attended the scientific sessions.66 [In that day and age, it was assumed that all “social registrants” would be female.] Despite these attractive features, attendance in Houston was slightly lower than at the Washington Meeting the year before.

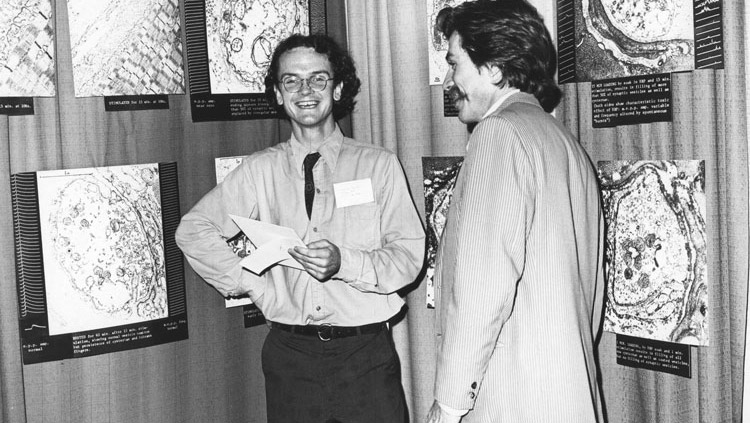

The 1973 Program Committee, chaired by Floyd Bloom, nevertheless determinedly planned a full docket at the third meeting, scheduled for November in San Diego.67 In addition to the usual presentations and public lectures, they also set aside time for special interest dinners, identifying a dozen different scientific subspecialties within neuroscience. There were clinically oriented groups, such as EEG, neuroendocrinology, sensorimotor integration, vision, and psychopharmacology; groups focused on experimental techniques, such as tissue culture and neuromodeling; and groups focused on brain function, chemistry, and structures: motivation, neurochemistry, neurotransmitters, memory, and morphology.68 The Program Committee’s efforts were an outstanding success; so many neuroscientists came to San Diego that a large number of sessions were standing room only and SfN President Walle Nauta asked Bloom to apologize to the attendees.69

Third Annual Meeting, San Diego, 1973

The Program Committees of the 1970s continued to experiment with new forms of presentations, including poster sessions, workshops, and demonstrations.70 By 1975, the Annual Meeting was large enough (3,775) that the Education Committee sponsored two neuroscience symposia, on neurotransmitters, hormones, and receptors: novel approaches. Seven papers were presented and then published by the Society.71 To continue the Society’s goal of giving neuroscience a public face, the planners regularly planned events for high school students and teachers at the meetings and extended invitations to local journalists.

TThe Council also introduced a spectrum of prizes to recognize outstanding achievements and to promote public interest and attendance. The first of these awards, presented in 1978, were the Donald Lindsley Prize for Young Investigators and the Ralph W. Gerard Prize for Lifetime Achievement. November 1976 featured a short course on neuroplasticity and recovery of function, presented the day before the Toronto Meeting. The short course required a separate registration, and 285 members participated.72 400 people attended the short course on neuroanatomic techniques two years later in St. Louis, while another 200 had to be turned away but could order copies of the syllabus “cookbook” for $4 from the SfN central office.73 SfN continued to offer short courses in conjunction with the main program and to develop innovative programs such as the neurobiology of disease workshop in 1989.74

SfN meetings were also taking on a more international dimension during this period. As one example, SfN and IBRO jointly sponsored a symposium on the reticular formation at the 1978 meeting in St. Louis.75

The Annual Meeting was a clearinghouse for job seekers and until 1977 there was a free bulletin board in the registration area that was always covered with job announcements. At the 1977 Meeting in Anaheim, SfN introduced a more formal Placement Service where, for a fee, employers and job seekers could register and schedule interviews.76 “Although the Society had to subsidize the first Placement Service by some $1,500, its success in assisting employers and candidates to fill job openings was so pronounced that the Council decided to continue it.”77

As the Society grew, the Program Committee’s task became more complicated, as the number of abstracts and themes increased from year to year.78 In the early days, members submitted all abstracts on paper and creating coherent sessions out of 15,000 abstracts for panels, symposia, and posters had become extremely challenging by the early 1990s. As Carla Shatz (President 1994–95) described her experience on the Program Committee in the 1980s, “there was this crazy shoot-out where we would all come to the Program Committee meeting with our stacks all in little piles and then we would have to put Post-its up on a wall and try to put our Post-its up to arrange…the schedule for the day so that…something from each theme was represented…It was hilarious.”79 The early small booklet of abstracts from the 1970s grew to two or more huge “telephone books” which members toted around at the meeting in the 1990s.80 SfN was one of the first organizations to offer a way to search the abstract database electronically; for the 1989 meeting, members could dial in to the database via modem and search by keyword, author, institution, or session title.81

Annual Meeting planners were quick to adapt new technologies for efficiency and novel forms of communication. At the 1977 meeting, Floyd Bloom coordinated the first satellite symposium, linking speakers in Anaheim with an audience in Washington, D.C., “to show that you didn’t actually have to physically travel to meetings in the future. You could actually attend by use of electronic means.”82

The Annual Meeting was an opportunity for interdisciplinary contact, but it was also a chance for special interest groups to meet and share ideas and techniques. Groups on circadian rhythms, new software, and reptile research met at one or more meetings. In 1985, the process was formalized and special interest meetings and dinners were organized around more clearly defined scientific topics.83

Other special interest groups explored the less formal side of neuroscience. At the Cincinnati Meeting, a few members met with a local folk dance group. “Looking ahead to the Los Angeles Meeting, they anticipated that a fair number of registrants who are active, closet, or potential folk dancers might be interested in establishing sensorimotor interactions with other neuroscientists.” They hoped to schedule a neuroscience folk dance evening workshop and asked interested parties to contact Andy Hoffer at NINDS with information about experience and which country’s dances they prefer and/or would like to teach.84 70 dancers attended the event, led by neuroscientists John Garti and Bob Lloyd. “Participants ranged from experienced dancers who often had a chance to test out rusty cerebellar circuitry established decades earlier to raw beginners.”85

Some neuroscientists made it a priority to stimulate their gustatory neurons. At the 1982 meeting in Minneapolis, there was an ancillary special interest dinner to explore “Capsaicin Burns at Both Ends: An evening of Sri Lankan Curry Cuisine…to introduce neurobiologists to one of the delightful uses of capsaicin practiced in Sri Lanka” followed by “a discussion of the present understanding of the neurotoxic effects of capsaicin on nociceptive transmission.”86 And after the 1989 meeting in Phoenix, Reuben Gellman organized a kosher neuroscience club so that those members who observed the kosher dietary laws could arrange for appropriate meals at the Annual Meetings.87

To succeed in its early years, the Society faced two seemingly contradictory hurdles. On the one hand, the founders hoped to tie together a disparate group of scientists with the conceptual thread of neuroscience, which at times seemed extremely slender. On the other hand, they saw the organization’s diversity as its strength and foresaw a society that fostered a kind of scientific “melting pot,” marbling together multiple national and disciplinary traditions and practices, reflecting the cultural ethos of its American birthplace. Efforts to maintain both diversity as well as unity would occupy much of the SfN leadership’s energies throughout the 1970s. But also during these early years, the Society found itself called on to define the organization’s stance on public issues – those in which neuroscientists had specialized expertise, such as lobotomy, as well as those that involved members as citizens of the world, such as the problem of Soviet dissident scientists.

Taking Positions on Public Issues

As part of SfN’s mission to represent neuroscience to the general public as socially beneficial and responsible in these early years, the Social Issues Committee alerted the Council to public debates, issues and controversies that were particularly relevant to neuroscientists or to international issues, that affected the scientific community. The psychosurgery debate at the San Diego Meeting in 1973 was SfN’s first such foray into public issues. Psychosurgery had become the topic of intense public scrutiny in the 1970s and was one of the most publicly visible issues confronted by SfN in this early period.89 As with later issues, the SfN approach included expert discussion, consensus polling of the membership, and the readiness to present itself as the scientific authority. The Presidential Symposium featured a debate over a ban on the practice, proposed by the Potomac Chapter and covered in The New York Times.90 In the membership vote that followed, 89% of respondents rejected “the idea of using psychosurgery for the solution of social problems, 73% thought it should be available with safeguards, 82% wanted more research with adequate safeguards, and 76% favored the establishment of a commission to promulgate guidelines.”91 In 1977, Robert Doty submitted this poll in testifying on behalf of the Society before the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects in Biomedical and Behavioral Research, and he presented SfN’s recommendation “that psychosurgery be made available as a procedure of last resort for the desperately afflicted patient, but only in a context where careful evaluation is possible over a long period of time.”92 The practice was largely abandoned by the 1980s.

Other examples of SfN response to public issues in this period included a 1972 debate at the business meeting of a member-proposed resolution regarding the Soviet Union’s emigration policy for Jewish scientists. These discussions forced the SfN leadership to define the boundaries of its democratic identity as they considered moral and ethical issues that were not strictly scientific but nonetheless had an impact on the scientific community at large.93 Although the Council voted to approve the statement, it also created a Resolutions Committee to vet such politically charged proposals in the future.94

The spectacular growth of SfN during the 1970s reflects the self-reinforcing confluence of several factors. First, leaders of SfN brilliantly encouraged diversity while, at the same time, creating a unified identity. Second, federal funding for neuroscience rose rapidly during this period, a fact not unrelated to SfN efforts. Using the NINDS budget as an example of the growth in neuroscience funding, Congressional appropriations to this institute increased from $97 million in 1970 to nearly $242 million in 1980.95 Third, neuroscientists had made a number of fundamental discoveries during this period of time. These discoveries not only merited nine Nobel Prizes by the year 2000, but also demonstrated the power of interdisciplinary efforts to understand the relationships between brain and behavior. The early SfN leadership wisely capitalized on this growing research capacity and scientific interest in neuroscience and invested it thoughtfully in programs that would further solidify and diversify the field. By the end of the first decade, the stage was set for the new discipline to come of age.

SfN Central Office and Staff

The Washington, D.C. area was the logical location for SfN headquarters and the organization relied on its close link to the National Academy of Sciences during its initial startup period. For two years, the SfN central office was located at the National Academy of Sciences on Constitution Avenue, before moving to offices in the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) building in Bethesda, Maryland. FASEB provided SfN with logistical support, particularly for the Annual Meeting, until the Society moved back into Washington, to 11 Dupont Circle, in January 1984. Three years later, SfN moved into larger quarters in the same building, remaining there until 2006, when the Society purchased its current building on 14th Street NW.96

From the beginning, the diverse and rapidly growing Society required a significant amount of clerical and organizational assistance. In the fall of 1969, Louise Marshall hired an Executive Secretary, who was the first and, for some time, the only paid staff member. The initial responsibilities of this job included keeping the minutes at Council meetings, coordinating communications for the Annual Meeting, and maintaining membership applications. The first Executive Secretary, Marjorie Wilson, served for 11 ½ years, hiring new staff to assist her as the workload increased; she was much beloved by the SfN leadership and members, and was awarded honorary membership in 1980 in recognition of her devotion and hard work.97

As the Society expanded, the staff grew along with it. By 1980, the staff included a membership director/bookkeeping manager, a publications director/newsletter managing editor, an administrative secretary, and a membership secretary. The executive secretary was replaced by an executive director with professional administrative experience, and a special projects coordinator came on board to work with the Committee on Animal Research and the Governmental and Public Affairs Committee. By 1987, there were a dozen individuals in six departments working in the central office at Dupont Circle. (see Figure 20); these gradually expanded to 50 staff in 12 departments by 1999.

SfN Budgets and Financial Growth 1970-1990

The Society treasurer’s annual reports, which were regularly published in the Neuroscience Newsletter, revealed the challenges of a growing organization. SfN in its first year, 1969–70, collected only $8,470 in member dues and relied heavily on a $20,000 grant from the National Academy of Sciences. Fortunately, its expenses were meager, only $6,288 for personnel and another $9,000 for office costs.98 Another grant from the Sloan Foundation provided an additional cushion the following year, which was needed since the first Annual Meeting set the Society back $4,736, and the second around $10,000. Beginning with San Diego in 1973, however, the Annual Meeting became a revenue generator, earning $20,000 for SfN that year. By 1975, with dues revenues at nearly $60,000 and meeting registrations at $53,000, Treasurer Martin Larrabee was able to report confidently that the Society had become independent of grant support and could maintain a 20% reserve.99

Building and investing a reserve became critically important in the late 1970s; although registration income continued to grow, the costs of printing the meeting program and abstracts book and distributing these to all members also increased, often exceeding Annual Meeting revenues. In fiscal year 1980, for example, Treasurer Bernice Grafstein reported that the costs of Annual Meeting and related publications had resulted in a $19,000 deficit, which would necessarily be covered from the capital reserve fund. Dues, grants, and other income from regular operations adequately covered regular operating expenses.100

Over the next decade, continued membership growth, income from exhibitors, and increasingly professional management put the Society on a more stable footing, despite occasional fluctuations. In 1989, the Treasurer was able to report an excess of $332,239 in revenues over expenses, and, in 1990, the lower but still healthy figure of $159,858. Membership dues and Annual Meeting revenues were nearly equal contributors to the total revenue of $3.8 million, but general operations expenses now exceeded Annual Meeting costs by $500,000, with printing and mailing costs outweighing even salaries.101 Still, maintaining a reserve and ensuring financial viability would remain a challenge for SfN until the new millennium.

Related

Endnotes

- Minutes of Second Council Meeting, January 22, 1970, p. 1, SfN Archive.

- Minutes of Third Council Meeting, April 15, 1970, p. 3, SfN Archive.

- “New Committee on Chapters.” NN 2:2, June 1971, p. 4; “Chapter Activities.” NN 2:4, December 1971, p. 4-5.

- Society for Neuroscience By-Laws, Article II: Membership, p 1, June 16, 1969. SfN Archives.

- “Taking Stock – An Editorial.” NN 3:1, March 1972 p. 2; LHM October 14, 1984 handwritten notes for talk in Anaheim – 2nd Draft, “History of the Society for Neuroscience, 1968-1994” Folder, Marshall Papers, UCLA-NHA.

- “Membership Committee.” NN 7:1, March 1976, p. 2, 4.

- “Progress Report.” NN 1:1, April 1970, p. 2.

- “Election Results.” NN 1:1. April 1970, p. 1.

- “Council Meeting.” NN 1:1, April 1970, p. 1.

- “Progress Report.” NN 1:1, April 1970, p. 2.

- Letter from Louise Marshall to David Cohen, February 11, 1977, “Society for Neuroscience To File 1977-1993” Folder, Marshall Papers, UCLA-NHA.

- “Editorial.” NN 1:1, April 1970, p. 2.

- “The Logo.” NN 2:2, June 1971, p. 2.

- “The logo.” NN 2:3, September 1971, p. 3 and 8.

- “The logo.” NN 2:4, December 1971, p. 8. The last issue of Volume 14 has a new layout and title banner.

- “First Annual Meeting.” NN 1:3, October 1970, p. 1.

- The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS), founded in 1948 as the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness, was renamed in 1968 when the National Eye Institute became a separate entity. From 1975, it was known as the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Deafness (NINCDS) and then became the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (again NINDS) in 1988, when the National Institute of Deafness and other Communicative Disorders was founded.

- “First Annual Meeting.” NN 1:3, October 1970, p. 1.

- “Taking Stock: An Editorial.” NN 3:1, p. 2.

- Ibid.

- Letter from Maxwell Cowan to Fred Worden, November 15, 1971, “Early SfN annual meetings 1969-1973; 1986 notes” folder, Marshall Papers, UCLA-NHA.

- Program, Society for Neuroscience Sixth Annual Meeting, November 7-11, 1976, p. 102.

- Interview with Floyd Bloom, May 6, 2014

- “Second Annual Meeting”Neuroscience Newsletter 3:1, March 1972, p. 1, 3.

- “Committees”NN 3:2 June 1972, p. 3.

- Second Annual Meeting Announcement and Press Release, September 15, 1972, SfN Archives. Preliminary Program, NHA, UCLA

- 1229 people were registered at the Second Meeting, compared to 1394 at the first. http://www.sfn.org/Annual-Meeting/Past-and-Future-Annual-Meetings/Annual-Meeting-Attendance-Statistics/AM-Attendance-1970s

- “ Special Interest Dinners”NN 4:3, September 1973, p. 1.

- Interview with Floyd Bloom, May 6, 2014.

- Programs, Interview with Floyd Bloom, May 6, 2014.

- Order Form for Neuroscience Symposia Volume 1, NN 7:2, June 1976, p. 7.

- “ Highlights of the Toronto Council Meetings” NN 7:4, December 1976, p. 2.

- “1978 Short Course Syllabus: Neuroanatomical Techniques”NN 9:4, December 1978, p. 7.

- Edward A. Kravitz, “Neurobiology of Disease Workshop”NN 12:1, p. 3–4.

- “1976 SN Annual Meeting Highlights”NN 7:3, p. 1; “SN 1978 Annual Meeting Announcements”NN 9:3, September 1978, p. 6.

- “Annual Meeting Notes: Placement Service”NN 8:3, September 1977, p. 6.

- “Society News”NN 9:4, December 1978, p. 7–8.

- Email exchange with Jack Diamond, January 9 and 13, 2014.

- Interview with Carla Shatz, November 5, 2018.

- Interview with James McNamara, November 5, 2018; Interview with Michael Goldberg, November 6, 2018.

- “Searching the 1989 Neuroscience Abstract Database”NN 20:5, September/October 1989, p. 8.

- RS interview with Floyd Bloom, May 6, 2014.

- See, NN 12:5, September 1981, NN 13:3, May, 1982, p. 8. 1985?

- “Neuroscience Folk Dance Workshop”NN 12:3, May 1981, p. 8.

- “Neuroscience Folk Dance Workshop”NN 13:4, July/August 1982, p. 7.

- “Errors in preliminary program”NN 13:5, September/October 1982, p. 4.

- “Kosher Neuroscience Club”NN 21:3, May/June 1990, p. 9; Interview with Abraham Susswein, November 2013.

- SfN data.

- Constance Holden, “Psychosurgery: Legitimate Therapy or Laundered Lobotomy?” Science New Series Volume 179, Number 4078, March 16, 1973, pp. 1109–1112, p. 1110.

- Harold M. Schmeck, “Research Backed in Psychosurgery” The New York Times, November 9, 1973.

- “Brain Death and Psychosurgery” and “Draft Position Paper on Psychosurgery”NN 4:3, p. 2–3; “Psychosurgery’s Torturous Path”NN 4:4, December 1973, p. 3; “Psychosurgery Finale”NN 5:2, June 1974, p. 6.

- Testimony of Robert W. Doty (Society for Neuroscience) in “Use of Psychosurgery in Practice and Research: Report and Recommendations for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Health” Federal Register Vol 42 NO 9 Part III, May 23, 1977, p. 26328

- Correspondence between Walle Nauta and Lawrence Kruger, October 31 and November 7, 1972, Society for Neuroscience 1972 Folder, Lawrence Kruger gift to UCLA Biomedical Library.

- Minutes of the 7th Council Meeting, November 7, 1973, p.1–2

- http://www.nih.gov/about/almanac/appropriations/part2.htm. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- NN 2:2, p. 2; NN 15:2.

- NN 12:3 May 1981 p. 7; Minutes of November 13, 1980 Council Meeting.

- Treasurer’s Report, Neuroscience Newsletter 1:3, October 1970: 3.

- Martin Larrabee, Neuroscience Newsletter 7:1, March 1976: 3.

- Bernice Grafstein, Treasurer’s Report, Neuroscience Newsletter, 12:2, March 1981: 1.

- Treasurer’s Report, Neuroscience Newsletter, 22:6, November/December 1991:2.