Chapter IX: Government and Public Advocacy: Not “Just a One-Day Affair”

SfN continued and expanded its role as an advocate for neuroscience throughout its second 25 years, developing and refining its strategies to have the greatest impact. The initial basic goal of increased research funding developed into a wider advocacy for scientific freedom in research, in the face of political challenges such as crusades against animal research and restrictions on the use of stem cells. Lobbying at the congressional and local levels continued into the new century, including the annual "Hill Day" and meetings during legislative recess; but SfN expanded in several directions, partnering with disease advocacy groups, training young members for careers in science policy and helping international partners to develop advocacy programs in their own countries. "Over time," Nick Spitzer (Chair, Public Education and Communication Committee, 2006-09) has commented, "we have learned how to be sophisticated, how to share the message."363

The closing years of the Decade of the Brain in the 1990s entailed some reassessment of this initiative. "It fostered, I think, greater cohesion, it was heady, it was exciting; but if the goal was to disproportionately increase funding of brain science it was also a failure," Spitzer observed.364 Yet there were long-term results – it contributed to a doubling of annual funding for the NIH starting in 1999; the first NSF grant program for neuroscience, announced in 2001; and the 2002 approval to build the Porter Neuroscience Research Center on the NIH campus, a new major site for brain science (the Center opened in 2014).365 The support of Rep. John Porter, a Republican, was indicative of GPA’s bipartisan approach: "We went against conventional wisdom on who might be supportive of NIH funded research and who might not be supportive, who might be supportive of science and who might not be supportive and we went across the aisle of all of our advocates and champions," John Morrison explained.366

As Nick Spitzer recalled, the DOB was the springboard for some important events, such as the April 1997 White House conference on Early Learning and the Brain, hosted by Hillary Clinton, showcasing SfN members Carla Shatz and Patricia Kuhl, and transmitted via satellite to nearly 100 sites in the US,367 and for some new partnerships, as when the first Advocacy Group luncheon at the 1996 Annual Meeting in San Diego brought SfN together with members of 20 disease advocacy groups.368

GPA Chair Joseph Coyle commented on his efforts to partner with these organizations: "If you're going to go to the government and ask support for brain research, they often say why and you say well, we can help cure brain diseases, well, that's what we're going to say, why aren't we there together with these people?"369 The decade’s end was marked by a major event at the National Academy of Sciences in April 2000, at which SfN leaders discussed recent research, Congressional advocates such as Senator Edward Kennedy expressed confidence in future government support for neuroscience, and Vice-President Al Gore and his wife Tipper and spinal cord injury advocate Christopher Reeve received the culminating DOB awards.370

One of the four major goals of the 2001-02 Strategic Plan was to "strengthen SfN’s role and influence in public affairs and advocacy" (see above). An early initiative was "CapWiz," an online action center that alerted members of pending legislation of significance to neuroscience and requested that they contact their Congressional representatives (later the Rapid Response Network). In March 2002, SfN appealed for support for the Helms Amendment to the Farm Bill, which excluded rats, mice and birds from some animal welfare regulations; members sent more than 1,360 faxes and e-mails and the Amendment passed and became law in May.371 The Annual Meeting that Fall included an Advocacy Forum, where speakers including Rep. Porter, Director Jon Miller of the Center for Biomedical Communications at Northwestern, and SfN advisor Frankie Trull, president of the Foundation for Biomedical Research [FBR], exhorted members that "Science advocates cannot do it alone... Go forth and advocate."372 The SfN further extended its advocacy partnerships when it joined with the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) to establish and contribute support for the American Brain Coalition, an organization of scientific and patient advocacy groups, in 2004.373

A Proactive Stance Toward Animal Research

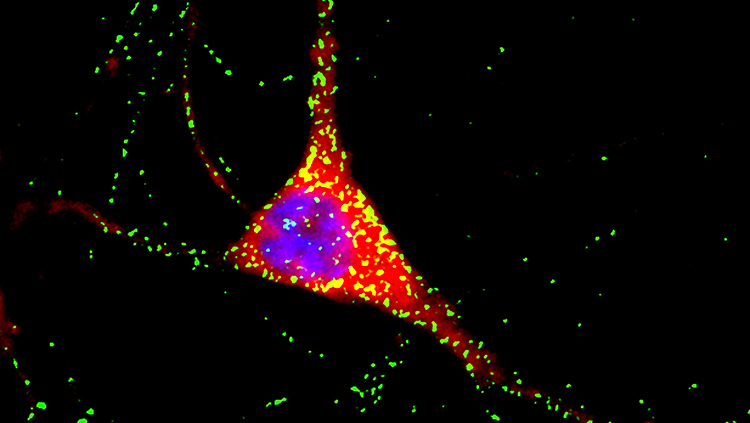

The defense of animal research continued to be an important focus in the 2000s. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and other animal rights groups were growing and establishing offices around the US by 2006, as well as in other countries, and the Internet had widened distribution of its ideology even further; these advocates had begun to develop the argument that animals were "persons," with the same rights as humans. Lawyer Michael Socarras explained at a 2003 meeting of SfN ally the National Association for Biomedical Research that the most effective defense to this argument was philosophical, not scientific, pointing out, for example, that animals lack a sense of morality.374 SfN’s Committee on Animals in Research (CAR), meanwhile, under Chair David Amaral, planned "a much more proactive approach," beginning with a new set of crisis management guidelines for researchers that emphasized a positive stance.375 The Committee decided, "[i]nstead of trying to fly under the radar in terms of the issues surrounding animals in research, we would educate the public, we would do outreach programs, we would be very up front about the fact that we do animal research and why we do it and what benefits emerge from it."376

CAR had also proposed the development of a list of Translational Research Accomplishments, illustrating the many positive benefits of animal research. The initial 2003 list, developed by an ad hoc committee chaired by John Morrison, included such examples as research on polio, retinal degeneration, depression, drug addiction, Parkinson’s disease, prions and the critical period for brain development.377

Translational Research Accomplishments was adapted into various formats, including a convenient wallet card edition (later entitled Animal Research Accomplishments) that members can carry in a pocket or purse, "so you're always prepared to advocate for animal research and how it impacts human health."378 Additional efforts to combat the anti-research message included a May 2005 forum, cosponsored with NIH and States United for Biomedical Research (SUBR), on educating teachers about "the nature of the threat to the appropriate use of animals in research, [disseminating] pro-research materials readily available to K-12 teachers, and [refining] the message the research community sends teachers about the use of animals in research;"379 and an 80-page handbook for medical students about the value and achievements of responsible animal research, a two-year project CAR began in 2007.380

SfN continued its strong advocacy on animal research in 2006 and 2007, years in which the Society recorded multiple activist attacks on individual researchers (6 in 2006, 11 in 2007). CAR Chair Jeffery Kordower stated forcefully that "[t]he continuing intimidation and threats of violence to which researchers have been subjected are beyond the bounds of acceptable discourse and debate.’381GPA and CAR successfully joined with NABR to lobby for the passage of the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act in November 2006, which enabled "federal authorities to help prevent, better investigate, and prosecute individuals who seek to halt biomedical research through acts of intimidation, harassment, and violence."382 The CAR chair became the key contact for SfN researchers who faced possible attacks; he and CAR members would contact the scientist and his/her home institution to advise on crisis management and support.383 In February 2008, SfN issued a new publication, Best Practices for Protecting Researchers and Research, directed to sometimes hesitant university officials, encouraging them to take a proactive public stance and to strengthen security measures to ensure researcher safety.

A few years later, in 2010, Responding to FOIA Requests: Facts and Resources advised members on Freedom of Information requests, often used by animal rights groups to identify and get information about protest targets, and best practices for response.385 In 2014, SfN and ABC organized a panel discussion for physicians and staff of patient advocacy groups to explain the critical role of animal research in developing new treatments for brain disorders.386 SfN meanwhile had participated actively in dialogues with NIH as it reviewed its regulations on the ethical use of nonhuman primates in research, culminating in a September 7, 2016, workshop in Bethesda, where participants emphasized the crucial role of these animals in research benefiting humans. NABR President Frankie Trull pointed out that primates represent only 0.5% of research animals, "[b]ut their impact on our health is enormous."387The Society reached out to help scientists in other nations as well, in 2016 submitting a letter to the Australian government to oppose a bill that would have banned the importation of captivity-bred nonhuman primates.388

The Challenge of a Shrinking Federal Research Budget

The NIH budget, meanwhile, had grown 14-15% each year from 199-2003. The 2004 budget saw a significant drop to a 2-3% increase, which the Bush administration proposed to continue annually, and SfN President Anne Young issued a "Call to Arms": "The Society for Neuroscience (SfN) must be engaged earlier in the budget process and fight harder for available research dollars," she wrote.390

In 2004, the Society, in partnership with FASEB (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology), joined the Campaign for Medical Research, provided funding for CMR’s ongoing efforts to inform and advocate with key Representatives and Senators on both sides of the political spectrum, and strengthened its relationship with the Joint Steering Committee for Public Policy (JSC), another coalition of biomedical research groups. Despite these efforts, the Bush administration proposed a second limited budget for research for 2005. SfN sent the first four publications in its Brain Research Success Stories series – stroke, depression, schizophrenia and PTSD – to legislators during Brain Awareness Week and briefed members on nine "talking points" they could use in writing to or speaking with legislators. These included the need for a "strong public health infrastructure," backed by "a high-quality science base" in the age of bioterrorism and global epidemics; the crucial need for research on diseases affecting baby boomers and the potential high cost of those disorders; and the "substantial dividend" already received from the federal investment in research.391 Positive signs at this time were California’s 2004 passage of a $3 billion ballot initiative to support stem cell research and NIH’s creation of a five-year blueprint for neuroscience research.392

The tight funding situation in the US persisted throughout most of the early 2000s, while restrictions such as those on stem cell research became prevalent. As Steven Burrill, Chair of CMR commented in 2007, "It’s tough to get anything funded…Core funding at NIH is not even keeping up with inflation, when we need an increase."393 In response, SFN’s new strategic plan of 2006 incorporated a "science policy strategy…an action-oriented plan to prevent further erosion of research prerogatives due to restrictive laws and regulations."394 Under GPA leadership, members continued regular visits to legislators and Administration staff from both major parties, using educational materials developed by GPA, and encouraged leaders in the biomedical industry to participate as well.395

The 2007 membership survey documented that some 535 members engaged in personal advocacy efforts, while a far larger number, more than 1400, participated by writing their legislators.396 Two new tools became available to them in July 2008: the SfN Advocacy Network offered members a monthly e-newsletter, updating them on legislative issues of importance to neuroscience, and enabling them to target their letters and contacts; while the Washington Research Update was a complementary publication for biomedical business leaders to keep them current on federal research funding trends.397 The Society’s message meanwhile became much more sophisticated. ‘I think what we've learned as a community is to control the narrative and to make sure we explain in more concrete and hopeful but realistic terms what the steps are between where our science is now and where it has to go," Nick Spitzer (Chair, Public Education and Communication Committee, 2006-09) explained.398 One key tactic taught to member advocates was the "elevator talk," learning to highlight in a few minutes, the length of an elevator ride, the aspects of one’s research of interest to laypeople.399

A Blackberry text message alerted GPA members at their Fall 2008 meeting that an Economic Recovery Act, just introduced in the Senate, included $1 billion in NIH funding, and the SfN advocacy team swung into action. That bill did not pass, but the ARRA Act of 2009 introduced under the Obama Administration, which received strong and immediate support in the form of 19,000 letters from SfN members, included $10.4 billion in increased NIH funding and $3 billion for NSF when signed into law in February. The GPA reminded members that one positive result was not enough and called on them to continue presenting the case for "sustained, bold science funding" in future years.400 The proposed Federal budget for FY2011 included a $1 billion increase in NIH funding, only enough to allow the agency to keep up with inflation, demonstrating the need for ongoing advocacy; the following year, legislators were talking about cuts in research funding. 401 In response, a new SfN publication offered suggestions to individual researchers for How to Host Congressional Lab Tours.402

The American Brain Coalition encouraged supportive Representatives to organize the bipartisan Congressional Neuroscience Caucus, led by Representatives Cathy McMorris Rodgers, a Republican from Washington, and Earl Blumenauer, a Democrat from Oregon; the inaugural event in June 2011 explained the basic science research helping to clarify post-traumatic stress disorder and Down syndrome.403 By 2016, Neuroscience Caucus members had participated in 17 briefings on subjects such as exercise and the brain, neurodegenerative diseases, traumatic brain injuries, basic science, and, in the wake of the Sandy Hook shooting in December 2012, the relationship between mental illness and violence.404

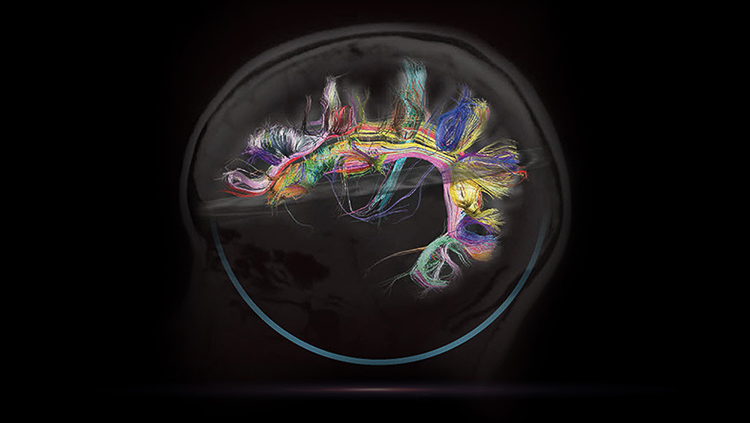

SfN’s sustained advocacy showed positive results in 2012, when the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy announced planning for a new Neuroscience Initiative, "a cross-agency effort... to discover significant, transformative opportunities across agencies and between the federal government and the private sector to advance the impact of federal investments in neuroscience to improve health, learning, and other outcomes of national importance." SfN leaders participated actively in giving the Initiative staff an overview of the field and its key issues.405 President Obama announced the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative in April 2013, with a planned FY2014 funding commitment of over $100 million, "the next great American project."406

After two years of discussions with scientists throughout the field, the working group’s report, "BRAIN 2025: A Scientific Vision," identified five target areas: perception, emotion and motivation, cognition, learning and memory, and action; and proposed an initial five-year investment in the development of tools and technologies, followed by five years of investment in discovery-driven science using those tools.408 The BRAIN initiative was exciting news for neuroscientists, during a period of sequestration and funding cutbacks affecting the federal research budget, in which researchers were often discouraged from submitting basic science applications, and pharmaceutical companies were shying away from brain research as "too difficult" and unlikely to earn profits within the immediate future.409

Still, in the late 2010s, "science budgets remain[ed] very anemic," as SfN President Steve Hyman told the membership in early 2015; he urged scientists not to "succumb to hopelessness…We are our own best advocates."410 SfN expanded its efforts to work with private funders and philanthropic organizations such as the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Wellcome Trust, and recruiting new manpower from among young members.411 In 2013, SfN named its first group of "Young Ambassadors," student neuroscientists given the opportunity to work with experienced advocates, participate in Capitol Hill Day, learn how to advocate with legislators and carry out advocacy projects, such as laboratory tours, in their home communities; in 2014, these young advocates were renamed "Early Career Policy Ambassadors."412 SfN has also developed a policy fellowship in which a graduate student or young scientist works on advocacy issues as part of SfN’s staff for six months and offers a webinar on careers in science policy.413 These programs make good use of the enthusiasm and energy of young scientists, while also giving them skills that will help them in planning their future careers.

"They can bring in the intellectual involvement and the intellectual ideas that they have learned through their graduate education and apply it to the betterment of human health and disease through reaching out to the public, but also at the same time reaching out to the politicians and Congress," Global Membership Committee Chair (2017-20) Ramesh Raghupathi explained.414

As SfN approached its 50th anniversary, its focus on advocacy remained strong, despite an unpredictable administration and contentious legislature. The BRAIN initiative continued, with similar initiatives taking shape in Europe, China and Japan.415 "Our advocacy cannot be just a one-day affair," SfN President Eric Nestler reminded his colleagues on Hill Day 2017; that year also saw the "March for Science" in Washington and 400 other sites around the globe.416 SfN also expanded efforts to reach out to Capitol Hill, inviting nine Congressional representatives and their staff to visit the poster floor at the Annual Meeting in Washington. The visitors were amazed and impressed by "the unbelievable size and scope of the conference"; one staffer remarked to an SfN member that he didn’t realize how close we were to living in the future."417 On "Hill Day" on March 7, 2019, 48 participants representing 24 states and six countries came to Washington, joining in more than 80 meetings and office visits to lobby Congress to increase NIH funding to $41 billion in the FY2020 budget.418

Related

Endnotes

- Interview with Nick Spitzer, November 5, 2018.

- Interview with Nick Spitzer, November 5, 2018.

- "NSF Launches First Neuroscience Program" NN 32 (Sept-Oct 2001): 14; "Government Affairs Update" NN 33 (May-June 2002): 10.

- Interview with John Morrison, November 5, 2018.

- "White House Conference Melds Neuroscience and Public Policy" NN 28 (July-Aug 1997): 1-2.

- "Society Brings Together Advocacy Groups and Members at Annual Meeting" NN 28 (Jan-Feb 1997): 5.

- Interview with Joseph Coyle, November 5, 2018.

- "Society Event ‘Neuroscience 2000’ Captures Attention of Policymakers, Public and Press; Helps Forge New Alliances." Neuroscience Newsletter 30 (May/June 1999): 1, 3, 28.

- "Government Affairs Update." NN 33 (May-June 2002): 11.

- "Experts Focus on Science Advocacy at Neuroscience 2002." NQ Winter 2003: 1-3.

- "American Brain Coalition Launches in San Francisco" NQ Summer 2004: 1. The ABC was originally founded by the American Academy of Neurology as the One Voice Neurological Coalition in 2001.

- "Latest Animal Rights Strategy: Animals as Persons," NQ Spring 2003: 1-2.

- "New Crisis Management Guidelines Will Help Members Deal with Animal Rights Activists." NQ Summer 2003: 13.

- Interview with John Morrison, November 5, 2018.

- "SfN Identifies Translational Animal Research Accomplishments," NQ Fall 2003: 11.

- "SfN Releases Translational Neuroscience Accomplishments in Wallet Card Form." NQ Summer 2004: 9; Interview with John Morrison, November 5, 2018.

- "Forum Addresses the Use of Simple, Positive Message to Teachers About Animals in Research," NQ Summer 2005: 5.

- "SfN Charts New Approaches to Combat Attacks by Animal Rights Activists," NQ Winter 2007: 1, 5-6.

- "New SfN Document to Help Universities Protect Researchers," NQ Spring 2008: 1, 12, p.1.

- "New Approaches," p. 6

- "New Approaches," p. 5

- "New SfN Document"

- "SfN Partners with Research Organizations to Provide FOIA Guidance," NQ Spring 2010: 1, 13.

- "Patient Groups Highlight Need For Animal Research," NQ Spring 2014: 9.

- "SfN Illustrates Importance of Nonhuman Primate Research at NIH Workshop," NQ Fall 2016.

- "SfN Supports Scientists Conducting Animal Research," NQ Spring 2016.

- "Message from the President: ‘A Call to Arms’ for Federal Biomedical Research Funding," NQ Winter 2004: 1-3.

- "2005 Funding Levels for NIH, NSF, and VA Do Not Keep Pace With Biomedical Research Inflation," Neuroscience Quarterly Winter 2005: 5.

- "President’s FY 2005 Budget Squeezes NIH, NSF, and VA," "Talking Points for Advocating for Biomedical Research," "Brain Research Success Stories Debut," NQ Spring 2004: 1, 6-9, 12.

- "Expert on Stem Cells Outlines Implications of California’s Stem Cell Initiative," "NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research Emphasizes Sharing of Resources and Expertise Across Institutes," NQ Winter 2005: 4, 6.

- "An Interview with G. Steven Burrill of the Campaign for Medical Research," NQ Fall 2007: 1, 5.

- "SfN Council Adopts New Strategic Plan to Renew Focus on Changing Needs, Ensuring to Serve Members Better," NQ Spring 2006: 4.

- "SfN Supports New White Paper Calling for Sustained, Increased Federal Support for Biomedical Research," NQ Summer 2007: 6.

- "Society Explores Changing Membership," NQ Winter 2008: 4, 16.

- "Advocacy: Engaging Members and Industry," NQ Fall 2008: 7.

- Interview with Nick Spitzer, November 5, 2018.

- "SfN Members Advocate for Increased Science Research," NQ Spring 2014: 8.

- "SfN Advocacy Supports Visionary Science Funding in U.S. Stimulus Bill," NQ Spring 2009: 1, 6-7.

- "Council Roundup: Spring 2010 Meeting," NQ Summer 2010: 5; "Council Roundup: Spring 2011 Meeting," NQ Summer 2011: 13.

- "Engaging Legislators in the Lab" NQ Summer 2010: 8.

- "Advocacy Update," NQ Summer 2011: 9.

- "Lawmakers Support Neuroscience on Capitol Hill," NQ Winter 2016.

- "Q&A: Exploring the White House Neuroscience Initiative," NQ Fall 2012: 4-5.

- Story C. Landis and Thomas R. Insel, "The NIH BRAIN Initiative," NQ Summer 2013: 1, 13.

- "About the Brain Initiative," https://www.kavlifoundation.org/about-brain-initiative.

- "Message from the President: The Promise of BRAIN," NQ Summer 2015.

- Ibid.

- "Message from the President: Becoming a Science Advocate," NQ Winter 2015: 1-2.

- "Message from SfN President Hollis Cline: Basic Science in the Pipeline," NQ Winter 2016.

- "Get Inspired to Advocate by SfN’s Early Career Policy Ambassadors," NQ Fall 2016.

- "Policy and Advocacy Careers: Making Change at a Large Scale," NQ Fall 2015.

- Interview with Ramesh Raghupathi, November 4, 2018.

- "Message from President Eric Nestler: Strengthen Your Focus on Advocacy," NQ Winter 2017. For more on global advocacy, see Section 7.

- "SfN Expands Advocacy Efforts to Amplify Need for Funding," NQ Spring 2017;

- "Policy Makers Connect with Researchers at Neuroscience 2017," NQ Winter 2018.

- "Spring Council Roundup," NQ Summer 2019.