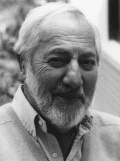

Seymour Levine

Gig passed away in his home in Davis, California on October 31, 2007. He was born in New York City of immigration parents in 1925. He joined the Army in 1943, stormed Omaha Beach in France on D-Day, and was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge. He was a devoted opera lover and lifelong San Francisco (ex-NY) Giants fan.

After earning a Ph.D. in Psychology from New York University in 1952, he held faculty positions in the Department of Psychiatry at Ohio State University 1956-1960, the Department of Psychiatry at Stanford University from 1962 until his retirement in 1995, and the Department of Psychiatry at U.C. Davis from 1999 until his death. He also served as Director of the Neurosciences Program at the University of Delaware from 1995-2000 and was a Ford Foundation Fellow at the University of London with Professor Geoffrey Harris from 1960-1962.

Dr. Levine had a prolific career which spanned over half a century. He made numerous pioneering contributions to the field of psychoneuroendocrinology and wrote and co-authored over 400 research papers in the field of developmental psychobiology. Of great importance to him were the international collaborations and projects he fostered and the mentoring of dozens of students and fellows. He received many honors including a Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Society of Psychoneuroendocrinology in 2000.

The early, novel ideas about ‘hormone releasing factors’ first motivated him to conduct research on neuroendocrinology. He later focused on developmental psychobiology, a subdiscipline that is almost synonymous with his name. Gig is appropriately considered to be one of the founding fathers of the ‘early experience’ concept. During the 1950s and 1960’s, this concept led to a radical shift in how we view the developmental antecedents of adult behavior and health by emphasizing the lifelong importance of formative experiences during early rearing. During the decades of the 1950’s - 70’s he opened the important field of research into the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis and its role in stress and infant development. He collaborated on many human projects up to his death, ranging from the influence of prenatal conditions on infant outcome to the evaluation of abnormal hormone responses in autistic children and cancer patients. He remained extremely productive until the end, and exuded just as much enthusiasm about these new undertakings as he did with his earlier work in his younger years.