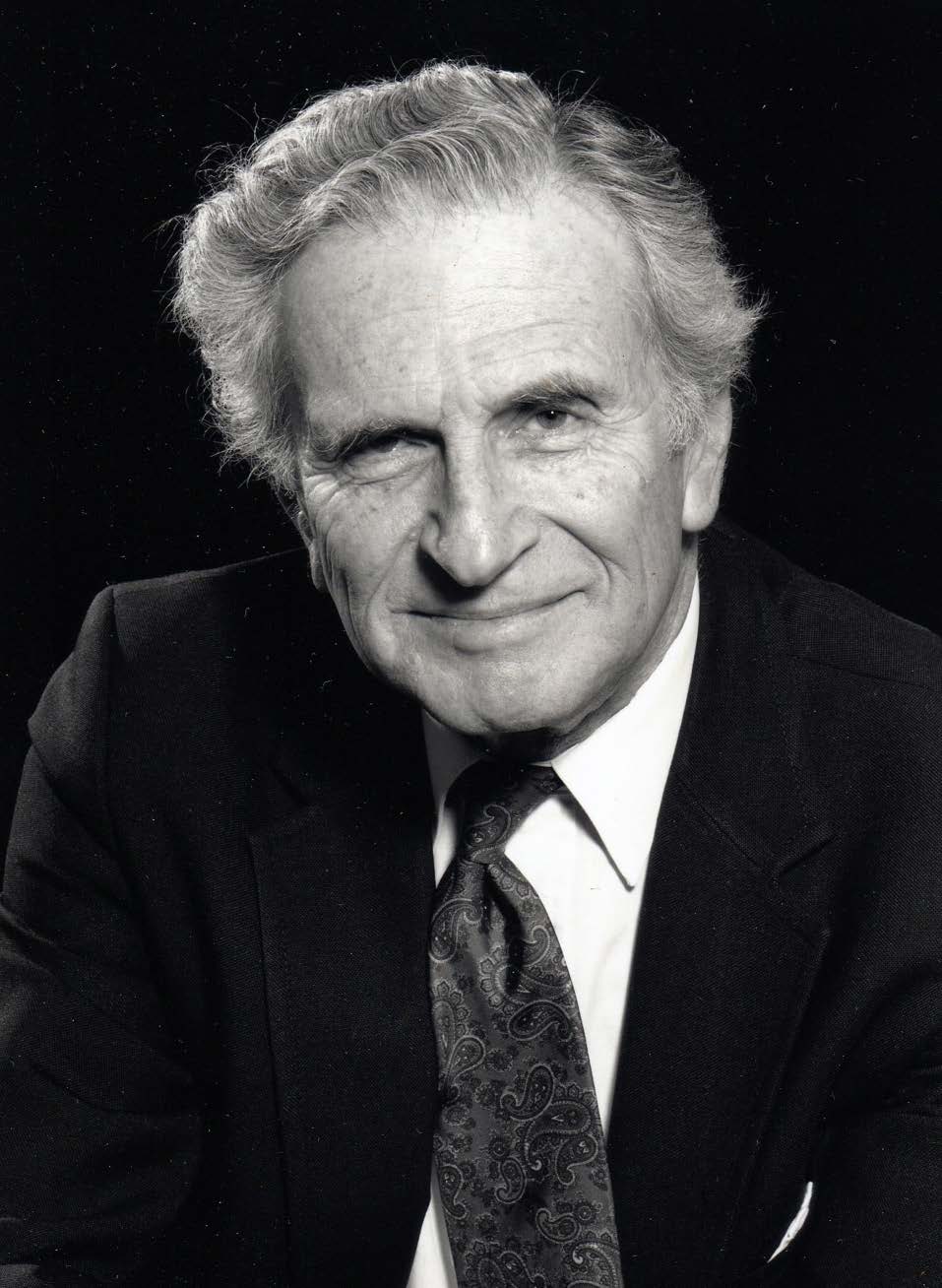

Arnold Scheibel

The field of neuroscience lost one of its most influential anatomists on April 3, 2017, with the passing of Arnold (Arne) Bernard Scheibel at the age of 94. He received a B.A. from Columbia College in 1944 and an M.D. from the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. After two years of psychiatric training in San Antonio, additional neuroanatomy training with Warren McCulloch in Chicago, and an appointment at the University of Tennessee Medical Center in Memphis, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship (1953-1954), which allowed him to travel through Europe, where he met many established neuroscientists, including Alf and Inger Brodal, Oscar and Cecile Vogt, and Giuseppi Moruzzi. During these travels, he also visited the Cajal Institute in Madrid, where he experienced firsthand the drawings and Golgi preparations of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, an event that shaped his research focus for the rest of his life. At the end of these travels, at the invitation of Horace Magoun, he accepted a joint appointment in the UCLA Departments of Anatomy and Psychiatry. He held this position for 55 years, and served as the Director of the UCLA Brain Research Institute from 1987 to 1995. As a researcher, he produced more than 200 groundbreaking investigations exploring the relationship between function and the fine structure of the nervous system. Although his story is captured elegantly in his 2006 autobiography, his passing provides us with an opportunity to revisit and appreciate his many accomplishments.

Arne’s research was always carefully conducted, and presented in an elegant writing style that incorporated the language of poetry to convey his scientific insights. With particular emphasis on Golgi neurohistology, he and his first wife, Mila, initially explored the fine structure of cerebellar climbing fibers and the organization of the inferior olive. These initial studies expanded to a broad series of investigations on the brain stem reticular core and the reticular nucleus of the thalamus, with an emphasis on functional contributions to selective attention, general arousal, and consciousness. From here, the research extended to the cerebral cortex, examining the termination patterns of thalamocortical and callosal axons on pyramidal neurons, and the giant pyramidal cells of Betz in the motor cortex. After Mila’s death in 1976, the research emphasis shifted. In addition to exploring the neural underpinnings of clinical disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease and Schizophrenia), these later years focused on the relationship between pyramidal neuron morphometry and cognitive functions. In particular, Arne and his colleagues documented positive associations between the computational demands in specific cortical regions and the dendritic extent of pyramidal neurons. This series of studies constituted a human parallel for the pioneering research of Marian Diamond at U.C. Berkeley, who had long been exploring the effects of enrichment on the brain in non-human animals. The overlap between Marian and Arne was more than professional, as they married in 1982, becoming a collaborative research force for the rest of his life. This collaboration is captured very appropriately in a loving tribute to Marian, namely the 2016 documentary by Gary Weimberg and Catherine Ryan: “My love affair with the brain: The life and science of Dr. Marian Diamond” (http://lunaproductions.com/brain/).

The broad reach of his scientific explorations notwithstanding, teaching was of prime importance to Arne (and Marian), and he wanted to be remembered as someone who enjoyed educating younger generations. This appreciation for teaching led Arne and Marian, in 1985, to collaborate on one of the most useful books available today for teaching human neuroanatomy: The Human Brain Coloring Book. Teaching was Arne’s forte, as was reflected in his reception of the UCLA Distinguished Teaching Award in 1997. He felt this pedagogical vitality was a quality imbued in him by his parents. His gratitude to them was expressed when he endowed two chairs at UCLA, one for his mother (the Ethel Scheibel Endowed Chair in Neuroscience in the Department of Neurobiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine) and one for his father (the William Scheibel Endowed Chair in Neuroscience at UCLA’s Brain Research Institute). A third endowed chair was funded in 2017 by neuroscientist Ron Hammer and neuropsychiatrist Sandra Jacobson, to jointly honor Arne and Marian (the Marian C. Diamond and Arnold B. Scheibel Chair in Neuroscience at UC Berkeley).

Although this narrative highlights some of his professional accomplishments, those of us who knew him well realize that the more personal side of Arne is what we will remember most. With that, we, as three former graduate students and colleagues, would each like to share a little more insight about Arne, the person.

I began my career in neuroscience as an undergraduate at UC Berkeley working with Marian Diamond. When it was time to choose a graduate training program, Marian suggested that I attend UCLA, but only if I could work with Arnold Scheibel. It was a difficult time for Arne as Mila would soon pass away, but he accepted me with additional mentorship in quantitative neuroanatomy from Bob Lindsay. With a storehouse of laboratory secrets on the mysteries of the Golgi stain (potassium dichromate and silver nitrate on the finger tips!), I began counting and classifying dendritic spines and defining dendritic structure in various human neuropathologies. Arne offered me the project that had brought him from psychiatry to neuroanatomy, exploring differences in hippocampal dendritic orientation in schizophrenia (his initial foray into this topic with Joyce Kovelman was published in Biological Psychiatry in 1984), but I decided to take a year to work and travel in India with the Berkeley Professional Studies Program. He supported my decision, stored my belongings in his Encino stables, and became my beacon from home in monthly letters exchanged par avion. I was pleased to learn that Marian had invited Arne to speak in Berkeley, and they finally met during my absence. On the way home, I visited Per Brodal at the Oslo Anatomical Institute and Victoria Chan-Palay at Harvard, connecting through Arne’s worldwide network of colleagues.

Upon my return, the UCLA lab was abuzz with activity on the neuropathology of aging, epilepsy, dendritic bundles and hippocampal structure, all illustrated through the graceful lens of Golgi’s method. I used a modified Golgi stain developed earlier in Arne’s laboratory by Larry Stensaas to demonstrate the normal development of brainstem reticular core neurons and their dendrites, a system which he had eloquently described as a stack of poker chips collecting information flowing through the brain stem to forewarn the cortex and various brain nuclei of pertinent input. Upon completion of my degree, Arne connected me with his colleague from the Neuroscience Research Program, Ed Evarts in the Laboratory of Neurophysiology at the National Institute of Mental Health, which opened for me a cornucopia of research opportunities in psychiatry. Arne not only fostered my own interest in the mechanistic basis of aberrant behavior, he provided a unique and visible perspective on the intricacies of brain structure, supervised my spouse, Sandra Jacobson’s clinical training during her psychiatry residency at UCLA, and fueled my eventual return to schizophrenia research. Thank you, Arne, for an introduction to your world of translational psychiatry (even before we knew what to call it!), for your friendship and mentorship, and for giving us a window to the nervous system and inspiring so many of today’s amateur and professional neuroscientists to dream about the workings of our own brains! Ron Hammer, University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix.

I joined Arne’s laboratory in 1979 without much understanding of neuroanatomy and even less of research. But I had two skills that I could offer: I knew how to use a scanning electron microscope (SEM) and I knew my way around a darkroom. Arne had already begun his morphological studies of the brain using the SEM. He and his research team at the time were prolific in producing neuronal images not seen previously. However, the SEM camera in those days was very basic. Control of lighting and contrast in the photos produced could only be achieved in the darkroom with much dodging and burning, terms that may be unfamiliar in today’s world of digital photography. This was my introduction to neuroanatomy and research, and Arne was instrumental in guiding my first steps. During the ensuing 38 years, Arne became integral to my life, as my dissertation committee chair, as my best man at my wedding, as my guide into the world of academia and always as a friend willing to listen, to give comfort at times of tragedy, and to share a laugh about the incongruities of life. His legacy will not only be his seminal contributions to neuroscience research and teaching but for all of us who were fortunate to know him, it was also his friendship that touched us deeply: Arne was a gentleman and a gentle man. Taihung Peter Duong, Indiana University School of Medicine.

I may have been one of the last graduate students to work in Arne’s laboratory, and I was certainly the least prepared. But, with Arne’s patient guidance and the continual support of my fellow graduate student, Taihung Peter Duong, I was soon enveloped in Golgi investigations. It is a path I have now been travelling for more than 30 years. Those who do Golgi research never lose the excitement of putting a freshly cover-slipped slide under the microscope to examine the mysteries revealed by each new impregnation. The road from Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal to Arne is very short (mediated by Lorente de Nó, Ramón y Cajal’s last student). I am honored to have been one of Arne’s disciples, and to have continued—in my own small way—working with the Golgi technique to explore quantitative neuromorphology in humans and other large mammals (e.g., African elephant, humpback whale, giraffe, and Siberian tiger). It was always a pleasure to share Golgi impregnations from these more exotic animals with Arne. Indeed, Arne has been with me every step of the way, both professionally and personally. I am indebted to him in more ways than I can even imagine. He was selfless, generous, and unwavering in his paternal support through the years, and his voice gently echoes through every neuroscience lecture I give to a new generation (even if they don’t recognize it). I will miss Arne’s laugh. He had the best laugh. Bob Jacobs, Colorado College, Colorado Springs.

In many ways, Arne’s Golgi studies presaged today’s magnificent illustrations of brain structure underlying behavior provided by CLARITY, and the current drive to explore the neural networks and circuitry of psychiatry. Carmine Clemente, then Editor of Experimental Neurology and Director of UCLA’s Brain Research Institute, once said that Arne Scheibel was the best “Golgi” neuroanatomist alive, and perhaps even the best neuroanatomist. We were already convinced, having experienced Arne’s Graduate Neuroanatomy course, which illuminated the beauty and complexity of the functional human nervous system for all of his students.

Read Arnold Scheibel's chapter in The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography Volume 5.