Sniffing COVID-19 Out: Studying the Nose to Understand the Coronavirus

Valentina Parma first noticed it on Twitter: A succession of complaints about lost smell back in mid-March. It was odd, recalled the psychologist and olfaction specialist at Philadelphia’s Temple University, because smell loss (anosmia) is often masked by or mistaken for other symptoms — people don’t tend to realize right away that it’s gone. Yet, here was a spate of people on social media claiming that their ability to smell had suddenly and definitively vanished. Equally astounding, many of them were blaming COVID-19.

Parma quickly realized she wasn’t the only olfaction scientist to be seeing this and banded with other experts to form the Global Consortium for Chemosensory Research — an international group of smell and taste researchers that distributed surveys in more than 30 languages to help describe the sensory losses seemingly associated with COVID-19. As the GCCR and other research groups began to take a closer look, it became clear that something bizarre was happening in noses around the world, sometimes in combination with disruption to taste and chemesthesis, the sense which lets us detect the cool of mint or the heat of spice.

Absence as Evidence of COVID-19

Early estimates on just how many COVID-19-positive individuals may experience anosmia ranged widely, but some experts suggest as many as 80% or more may exhibit some form of olfactory, taste, or chemethesis dysfunction. For some, smell loss is the only symptom they experience, and one study found that anosmia was a better predictor of a positive COVID-19 diagnosis than other common symptoms including cough and fever. Experts have suggested too that the nose — the doorstep to the brain — might hold clues about how COVID-19 could affect the nervous system at large. The findings have prompted a rush of research to determine just what COVID-19-driven anosmia can tell us about how the illness progresses and how to track disease spread.

“My hope is that you could you perhaps determine if a person is going to develop COVID based on very subtle changes in smell and taste,” Parma says.

Various research groups have now seized upon the hope that smell-based detection tests might help diagnose COVID-19 and are racing to develop home smell tests to help alert people when they need to self-quarantine. Mark Albers, a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital who studies smell deficits as a potential early warning sign for Alzheimer’s disease, has been working to adapt his lab’s mail-able peel-and-sniff smell tests for COVID-19. Such tests can also help document the range of possible smell symptoms that might come along with COVID-19, allowing scientists to answer questions like how many people lose their smell completely and whether certain subgroups don’t get it back.

Novel Virus, Novel Mode of Action

SARS-CoV-2 is not the first coronavirus humanity has grappled with. The best-known examples are an endemic family of bugs that cause the common cold, which — as almost anyone can attest — can lead to temporary disruption of smell. But that disruption comes along with congestion, a flood of inflammation that can block odor molecules from reaching olfactory receptors tucked deep inside the nose. Smell usually returns when inflammation resolves. On the rare occasions that it doesn’t, it’s because the attack was severe enough to kill off the olfactory neurons, which can leave patients without smell for months to years, as new cells regrow long processes that must crawl up the back of the nose and attempt to find their way to their target connections in the olfactory bulb.

But COVID-19 anosmia doesn’t fit either of those patterns. Most patients report smell disruptions in the absence of congestion, and those who lose their smell tend to regain it in a matter of weeks, not months as would correspond to olfactory neuron death.

“All of this suggests that whatever the SARS-coronavirus-2 is doing, it's doing something different than the typical cold-causing viruses,” said Robert Datta, a neurobiologist and physician at Harvard Medical School, at a June 3 meeting of the Congressional Neuroscience Caucus.

To try to figure out what might be happening, Datta and his colleagues dug through existing genetic datasets to determine what cells in the nose might express the ACE2 receptor that SARS-CoV-2 targets. They found that olfactory neurons themselves do not express ACE2 receptors, but other cells responsible for protecting and supporting the olfactory neurons do, including Bowman’s gland cells, which secrete mucus, and sustentacular and microvillar cells, which likely serve a range of functions including structural and energetic support. Perhaps damage to these cells is disrupting part of the process that allows us to smell.

“Frankly, that’s pretty good news,” says Datta. “It means that in most cases, the virus is unlikely to be altering the key neurons that are responsible for odor processing. This might enable most patients, ultimately, to recover.”

A Pathway to the Brain?

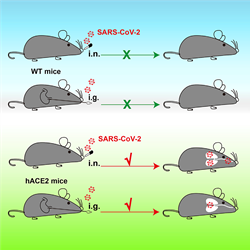

Mouse models expressing human ACE2 display infections in the brain. Source: Sun, S., Et al. (2020). A Mouse Model of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Pathogenesis. Cell Host & Microbe, 28(1) 124-133.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.020

Still, scientists think that continuing to study what’s happening in the nose might yield clues to whether the virus can enter the brain and what kind of damage it might do there.

“It's sort of a window into the brain because it’s something you can relatively easily access,” says Marco Hefti, a neuropathologist at The University of Iowa in Iowa City. The nose can also be a pathway into the brain for viruses, he says. It’s not clear if in rare cases, SARS-CoV-2 might be able to hop from the nose to the brain as scientists believe happens in other viruses, like chikungunya, polio and other human coronaviruses, which don’t target ACE2. In one study SARS-CoV-2 nasal exposure led to infection in the brain in a mouse model expressing human ACE2 where mouse Ace2 is normally present. But little evidence exists for this happening in humans.

Whatever the cause of smell symptoms may be, Parma expects that we may start seeing more people who lose smell permanently, a condition she considers underappreciated in its ability to disrupt normal life. Though we go through much of our life barely aware of our sense of smell, losing it can completely throw off our sense of wellbeing, Parma says. Inability to smell is linked to higher rates of anxiety and depression and can leave people feeling unable to enjoy day-to-day experiences as fully as they once did.

“Food is bland — it feels like you’re eating cardboard; you cannot enjoy the smell of flowers; you cannot enjoy the smell of baked cookies; you cannot enjoy the smell of the people you love,” says Parma, who urges experts to be aware and prepared for the potential need to step up support for such patients through focused research and health care. “Potentially after COVID we'll have a lot of more people [going through this] than we had before.”