Why the Brain Loves Stories

To celebrate SfN’s 50th anniversary, each 2020 issue of Neuroscience Quarterly will delve into the science behind one of SfN’s four Mission Pillars — statements of the Society’s strategic goals.

Carrying out SfN’s Mission Pillar “Educate and engage the public” requires connecting with non-scientists. This article explores how the brain processes stories, a powerful tool when communicating with others.

The brain is a story junkie. No matter how much information it wades through, the brain seems to latch onto and remember stories above anything else. If you have ever neglected your responsibilities to stay up until 3 a.m. binge-watching a new TV series, you have experienced the power of a good narrative.

Rae Nishi witnessed this power firsthand. During her tenure as a professor at the University of Vermont, Nishi participated in Community Rounds, an opportunity for local business owners, legislators, and other community leaders to learn about the research conducted at the university. Most professors would show slides about their work, but Nishi mixed things up and brought people to her lab.

Nishi showed the community leaders cultures of neural cells and told stories about the day-to-day interactions in the lab – especially with her husband’s lab residing next door. “They were curious about how we manage a husband and wife team doing research and keeping the peace.” Compared to the slide presentations, Nishi noticed a marked difference in her audience when she shared her story. They looked and nodded at her, asked more questions, and listened attentively. “That’s a subtle change you don’t necessarily see when you’re just presenting data.”

But why does the brain find stories more engaging? Why are data not enough? As with any mystery involving the brain, neuroscientists want to find out.

The Narrative Hub of the Brain

The brain processes stories differently from other forms of communication. “[Stories] are a whole other category of how we can share information, that seems to be prioritized,” says Liz Neeley, executive director of Story Collider, a science storytelling nonprofit based in Washington, D.C.

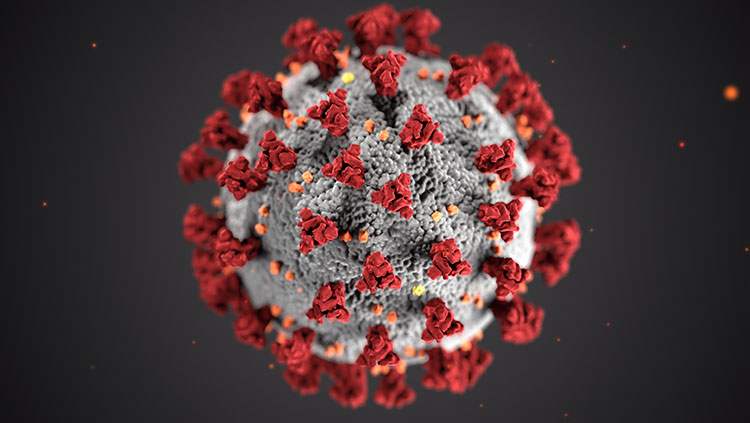

Telling a story, no matter the medium, activated a “narrative hub.” This includes (from left to right) the posterior cingulate cortex, the temporoparietal junction, and the posterior superior temporal sulcus. Source: Yuan et al., Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 2018.

Characters may be why humans love stories: they activate the brain’s hard-wired social processing. Social experiences recruit the mentalizing network, a group of brain regions that predict the motivations, emotions, and beliefs of other people. These regions are also part of a “narrative hub” activated by telling a story (1). Yuan et al. measured the brain activity of artists while they shared the contents of brief headlines through words, drawings, or gestures. The headlines described a character completing an action, such as “Surgeon finds scissors inside of patient.” Across all three mediums, story production activated several brain regions from the mentalizing network: the temporoparietal junction, the posterior cingulate cortex, and the posterior superior temporal sulcus.

Even though it was not part of the instructions, the participants focused on the character and their mental states. While telling a story, the brain attends more to what a character is thinking or feeling as they complete an action, rather than on the sequence of actions itself — character trumps plot.

The Evolutionary Origins of Storytelling

The social component of stories also explains why they emerged in human evolution. Humans have told stories since the beginning of language. Our ancestors used stories to collectively process complex concepts, convey important information, and connect with each other. Stories are also an effective way to influence behavior and may have evolved as a way to pass down behaviors that increase fitness (2). “Stories are more engaging, so people want to listen to them in the first place,” says Neeley. “People understand information packaged in a narrative format better than other formats, so stories are more likely to be persuasive and believable.”

Part of the power of stories comes from narrative transportation (3), “that delicious feeling of being sucked into a story world,” says Neeley. Compared to rhetorical arguments, narrative transportation elicits stronger emotional reactions, increases information retention, and causes greater attitude and behavior changes (4). Telling a story is often the best way to share information and increase the likelihood it is remembered.

Stories are an effective tool for sharing complex information, but can researchers use stories to share their work? Evidence suggests that scientists should talk about the thing they have been trained to remove from their science: themselves.

Telling Stories as a Scientist

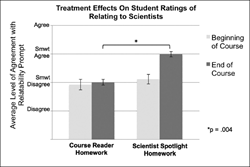

“The simple act of hearing a scientist’s personal story has profound impacts on a person’s perception of and interest in science.”The simple act of hearing a scientist’s personal story has profound impacts on a person’s perception of and interest in science. A study in community college students taking Human Biology found that incorporating “Scientist Spotlight” homework assignments into the curriculum corrected scientific stereotypes, improved grades, and increased interest in science (5). These assignments featured biographical profiles of a diverse group of scientists and asked students to reflect on the stories. In a survey administered before the semester, students described scientists as “intelligent” and “people that do experiments.” After the semester, nearly half of the students that completed Scientist Spotlights assignments described scientists as “all types of people.” One student elaborated “all types of people can do science…your background/sex/race doesn’t determine if you will become a scientist or not.”

Before the semester, only 35% of students felt they could relate to scientists. After the semester, 79% of Scientist Spotlight students found scientists relatable, while the same was true for only 49% of students following a typical curriculum (Course Reader). Source: Schinske et al., Life Sciences Education, 2016.

Hearing the personal narrative of scientists tore down existing stereotypes about the field, resulting in higher grades and increased interest in a scientific career. Most of all, the students saw scientists as not so different from themselves. Before the semester, only 35% of students felt they could relate to scientists. After the semester, 79% of Scientist Spotlight students found scientists relatable.

Nishi experienced this when she shared her story of doing science alongside her husband. “If you let the person or audience you’re talking to know that you’re a person just like them, and you can talk just like them… you break down that barrier of science. The biggest thing is to let people know I am just like you — I just have this other area of technical expertise. I can’t sew worth beans, but I can do a PCR, but that doesn’t mean I’m any better than you.”

“I think that having the full spectrum of lived experiences in research, in science, in neuroscience, helps showcase science for the fundamentally human process that it is.”Building these personal connections can make people more receptive to hearing about your work and encourages them to engage with the field more broadly. In a way, storytelling acts as a critical tool toward making science inclusive and accessible to all. “I think that having the full spectrum of lived experiences in research, in science, in neuroscience, helps showcase science for the fundamentally human process that it is,” says Neeley. “It helps us narrow the gap between what we strive for, the values we claim, and the reality of the culture, the labs, the universities, and the institutions that collectively we call science.”

Narratives wield power on both the large and small scale. Storytelling scientists can facilitate the creation of a more inclusive and diverse field. But, as Nishi experienced, stories also help your audience connect with you and engage with your research. Whatever the goal, the story of your life and work is one that you can tell better than anyone — so start telling it.

To learn more about weaving together science and storytelling, check out the storytelling resources available from Neuronline:

Scientific Storytelling: How to Win Hearts and Minds