Inside Neuroscience: Studies Show How Early-Life Experiences Affect Brain Development

Elizabeth Cox, a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University, and Scott Mitchell, a graduate student at Dundee University in the United Kingdom, present at a Neuroscience 2014 press conference on the developing brain.

Starting in the womb and continuing through adolescence, experiences shape the brain. Many mental health issues affecting society — including addiction, anxiety, depression, and autism — are influenced by early-life experiences, which put some people at higher risk for developing mental health issues later on.

During a press conference at Neuroscience 2014, researchers studying the developing brain revealed how stress during pregnancy or trauma during childhood can have profound negative consequences later in life, while bonds with caregivers can augment brain development. The findings “highlight the mechanisms by which early experience — and particularly the role of parents in early experience — shape our later development into adolescence and beyond,” said Martha Farah, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania and moderator of the press conference.

Prenatal Exposure to Pollution and Stress Increases Anxiety in Mice

Prenatal exposure to high levels of air pollution is associated with increased risk for anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and autism. Other factors, such as maternal stress, may combine with pollution to increase risk. For example, stress during pregnancy can reportedly exacerbate the effects of exposure to toxins such as tobacco smoke. Jessica Bolton, a graduate student in Staci Bilbo’s laboratory at Duke University, wanted to better understand the combinatorial effect of environmental toxins and stress.

Four groups of pregnant mice were exposed to control conditions, air pollution (diesel exhaust particles), maternal stress (less nesting material), or both pollution and stress. Offspring prenatally exposed to either pollution or maternal stress alone showed behaviors comparable to control mice in tests of contextual fear conditioning and anxiety-like behavior. In contrast, mice prenatally exposed to both pollution and maternal stress had increased anxiety-like behaviors.

Male offspring subjected to both pollution and stress also displayed memory deficits. Bolton noted this sex difference makes sense given that some neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism, primarily affect males.

Bolton further hypothesized that environmental toxins and stress might share a common mechanistic pathway by both acting on the immune system. Indeed, male mice exposed to both pollution and stress had higher levels of proinflammatory molecules, such as interleukin-1β and toll-like receptor 4, in the brain compared with mice in other groups.

“Maternal stress during pregnancy can unmask the effects of the air pollution exposure on the developing brain,” leading to long-term behavioral consequences, Bolton said.

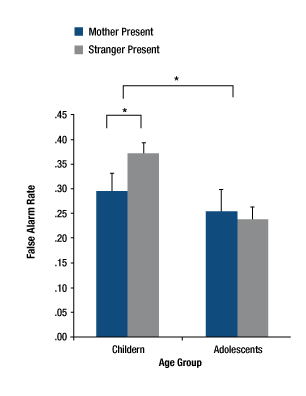

Children and adolescents performed an emotional regulation task in the presence of their mother or a stranger, and researchers measured the rates of incorrect responses for each group. Children made fewer errors in the presence of their mother. In contrast, adolescents performed equally well whether they were seated with their mother or a stranger. Courtesy of Dylan Gee.

Mother’s Presence Alters Circuits Involved in Regulating Emotions

While stress and abuse can negatively affect the young brain, social relationships may buffer their effects on brain development. In adults, connections between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex help regulate emotion, but these circuits mature late in development. How emotion is regulated earlier in development remains unknown. Dylan Gee, a graduate student in clinical psychology in Nim Tottenham’s lab at the University of California, Los Angeles, wondered whether the presence of a caregiver provides an external source of emotional regulation.

To test her idea, she scanned the brains of children and adolescents while they viewed either a picture of their mother or a stranger. Outside the scanner, the participants also performed an emotional regulation task while seated with their mother or a stranger.

Compared with viewing or sitting with a stranger, children had stronger connections between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex and made fewer regulatory errors in the presence of their mother. In contrast, adolescents showed no differences in the presence of their mother vs. a stranger, presumably because the circuits involved in regulating emotion were more mature.

When their mother was present, the children’s brains resembled those of adults. Additionally, “children whose mothers had greater effects on their amygdala-prefrontal connections also had lower anxiety and more secure parent-child attachment,” Gee said.

GABA Receptor Subtype May Link Early-Life Stress to Addictive Behaviors

Stress during early childhood has been associated with increased risk of drug addiction later in life. Previous genetic studies implicated a variant of the α2 subtype of the GABA-A receptor in mediating the increased risk. Scott Mitchell, a graduate student in Delia Belelli’s and Jeremy Lambert’s laboratories at Dundee University in the United Kingdom, wanted to identify a biological mechanism to explain the connection between the receptor subtype, childhood trauma, and addiction.

To uncover such a mechanism, Mitchell and colleagues injected three groups of mice with cocaine. With every injection of cocaine, wild-type mice ran further around a circular track, an addictive-like behavior. Mice lacking the α2 subtype of the GABA-A receptor, however, had an even greater response to cocaine, running as much after a single injection as the wild-type mice did after 10 injections.

Mothers of the third group of mice were given limited nesting material during nursing, causing them to spend less time with their pups. This early-life stress had the same effect as the missing receptor subtype: Partially neglected mice also had an increased response to cocaine. Furthermore, staining and electrophysiology in the nucleus accumbens revealed a selective decrease in the α2 subtype of stressed mice.

According to Mitchell, these data suggest that “early-life trauma is reducing a key GABA-A receptor subtype within the nucleus accumbens, which is a key area of the reward pathway, and this then alters the response to acute and repeated cocaine administration.”

Childhood Abuse Affects Brain Circuits Regulating Emotions and Impulses

Early-life trauma also has long-lasting effects in humans. Adolescents who were abused or maltreated as children have higher rates of emotional problems and risky and addictive behaviors. Studies have indicated that maltreatment affects the circuitry of the prefrontal cortex, an area that matures during adolescence and helps regulate emotion and impulse control. However, it is unknown whether these changes occur before or during adolescence.

Elizabeth Cox, a postdoctoral fellow in Hilary Blumberg’s laboratory at Yale University, studied the scans of brains of adolescents who reported being neglected or abused during childhood. They were scanned twice, around age 15 and again about two and a half years later.

Compared with previous results from normal adolescents, the prefrontal cortex decreased in volume over the time period. The second scan also revealed that the prefrontal cortex had reduced integrity of white matter tracts and decreased responses to emotional stimuli. Additionally, adolescents who reported higher levels of childhood maltreatment displayed greater changes. There were gender differences as well: Girls showed greater decreases in circuitry relating to emotional regulation, while boys showed greater decreases in circuitry responsible for impulse control. According to the researchers, these preliminary findings may explain previous research suggesting maltreated girls are more likely to suffer depression while maltreated boys are more likely to abuse drugs.

The research suggests that the effects of abuse are established during adolescence, indicating that “adolescence may be a window of opportunity during which possible interventions may hold promise for preventing some of these outcomes in these kids,” Cox said.

Understanding Who We Later Become

“Overall, from the molecular level through the activity of large-scale brain systems, we are beginning to understand the effects of early-childhood experience — even prenatal exposure — on who we later become,” Farah said. The researchers agreed that further research could lead to treatments and interventions to prevent damage and promote healthy brain development in early childhood.