Thriving in the Era of Team Science

As neuroscience becomes more interconnected and expansive than would have been thought possible 50 years ago, team science — collaboration between researchers from multiple labs, fields, and industries — is quickly becoming a critical component of scientific discovery in the 21st century. The unique challenges team science presents individual researchers, and the need for neuroscience institutions to shift how they perform and reward good science, were discussed during two workshops at Neuroscience 2019.

New Challenges, New Skills

How can scientists overcome the inherent challenges of working with large, distributed teams?

A. Bolu Ajiboye of BrainGate2.0 presenting at the Navigating Team Science workshop.

Three PIs shared tips toward the success they enjoyed while working on large-scale, collaborative projects during the “Navigating Team Science” workshop, organized by SfN’s Professional Development Committee (PDC). These projects include the International Brain Laboratory (IBL) to create the first brain-wide neural map of decision making, the FES Center and BrainGate2.0 to develop new machine-brain systems, and the Collaborative Center for X-linked Dystonia Parkinsonism (XDP) to educate researchers on, and provide care for, patients.

While discussing what made their projects successful, the PIs all emphasized communication. For leaders, this meant balancing the priorities and skillsets of scientists from different institutions, providing a clearly defined mission and organizational structure, and bringing all parties into agreement on data sharing, clinical trials, and authorship.

For early career researchers, this means making themselves heard. In large teams, it can often be difficult for trainees to distinguish their independent career.

“Team science is exciting… but there are risks for trainees,” explains Chiara Manzini, who co-organized the “Navigating Team Science” workshop. “As they enter a large project, it is important that they ask how their contribution will be highlighted and how they will be supported in their future career transitions.”

The PIs offered ways senior scientists can aid early career researchers. Becoming a sponsor for trainees, organizing small team meetings to discuss their contributions, and including their opinions in new hiring decisions are all ways that leaders can support trainees through team projects. They also urged trainees to be confident in their work and the contributions they can make to a team.

“It’s important to keep in mind that as a student or postdoc, your voice is really important.”Anne Churchland

International Brain Laboratory

“It’s important to keep in mind that as a student or postdoc, your voice is really important,” said Anne Churchland of IBL during the workshop Q&A. “Most organizations would benefit greatly if younger people lowered this threshold of what it takes to speak up and ask questions or suggest a new idea.”

How Institutions Can Reward Collaboration

Adjusting to team science goes beyond individuals. At “Hiring and Promoting Faculty in the Era of Team Science,” a workshop organized by SfN’s Neuroscience Training Committee (NTC), institutional leaders from the Broad Institute, Scripps Research Institute, and Allen Institute for Brain Science discussed the institutional barriers that researchers currently face.

What they found was that in a field becoming increasingly collaborative, institutional practices largely use outdated measurements of success that can leave large numbers of early career scientists behind. Between 2008-2018, for example, the percentage of multi-PI grants increased by 16%. The average number of authors per citation has also steadily increased from two to six since 1975. Despite these changes, institutions often rely on highly individualistic criteria for hiring and promotion.

Roz Segal

Harvard Medical School

“While much of science is now carried out in a team, most universities, institutions and prize committees want to identify a person as the one responsible,” said Roz Segal, moderator of the workshop. “A job, a promotion, nomination to an elected society, or a prize award, is awarded to an individual. In team science, it is unclear who is responsible, and so who deserves credit. In many cases, from a team, the senior person and those most adept at self-promotion are the ones that are accorded credit.”

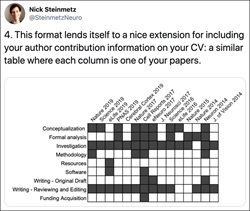

Saskia De Vries of the Allen Brain Institute presented a Visual Matrix like the one proposed by Nick Steinmetz.

The speakers offered a number of ways institutional leaders can address the stigma against collaboration. These include: deemphasizing impact factor (which has been found to be prevalent in review, promotion, and tenure documents of universities in the U.S. and Canada); promoting team science through seed grants and greater focus on interdepartmental and clinical-basic research; and including collaboration in evaluation criteria for hiring, awards, and promotions. Another thought-provoking solution is to rethink how authorship is displayed. Rather than a list format that emphasizes first and last author, Saskia de Vries of the Allen Institute presented a “visual matrix” model proposed by Nick Steinmetz using taxonomy from CRediT. The model allows authors to be clearly recognized for their specific contributions, from conceptualization to funding acquisition to review.

The Future of Team Science

Team science poses other challenges. Workshop attendees also asked about discrimination, the impact of social media, and differing cultural attitudes between institutions — all complicating factors that will need to be addressed as the field becomes more collaborative.

The issues raised by team science are beginning to be addressed by organizations like SfN and the Allen Institute, as well as initiatives like SfN’s NINDS-supported program — a program to address systematic barriers in neuroscience, of which the NTC workshop was the first event. But there is more to be done.

“I sense a new urgency in attacking the big questions and problems in neuroscience,” says John Davenport, moderator of the “Navigating Team Science” workshop and facilitator of an upcoming live chat on the same topic this February. “Scientists are anxious to make real headway against ALS and Alzheimer's, are concerned about the opioid epidemic, want to reduce suicide, and want to truly understand how huge numbers of neurons and other brain cells work together. People see the huge potential of faster progress by working in teams.”

By creating a scientific community that encourages and supports effective collaboration, individual and institutional members of the neuroscience community can accelerate their personal careers, institutional achievements, and the pace of discovery.