Inside Neuroscience: GLP-1 Agonists on Dementia, Pain, and Motivation

Popular weight loss and diabetes drugs such as Weygovy and Zepbound seem to be multitaskers.

Beyond their initial Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indications to quell food intake and control diabetes, GLP-1 agonists have been approved to treat sleep apnea. Ongoing clinical trials are testing them for conditions such as substance use disorder, arthritis, dementia, and depression. And preclinical studies in rodents are uncovering other potential actions.

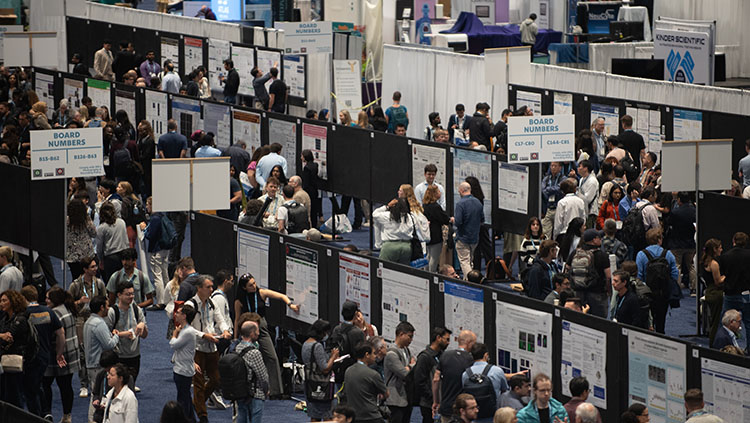

At Neuroscience 2024, scientists shared results from several preclinical studies in a press conference titled “The Brain on GLP-1 Agonists.” The studies revealed GLP-1 agonists’ impact on Alzheimer’s disease, pain relief, and exercise and motivation.

Karolina Skiblicka

The drugs affect the activity of brain regions involved in modulating food intake by binding to GLP-1 receptors located there. But such receptors are also present in many other areas of the brain.

“The brain is the main target of these new blockbuster drugs,” said moderator Karolina Skiblicka, a neuroscientist at the Pennsylvania State University. “Because they are so effective at targeting multiple brain areas, there are also other things that they could potentially be doing.”

Testing Weight Loss Drugs in Alzheimer’s Models

Early studies in people and animals have hinted that GLP-1 agonists may have an effect on neurodegenerative disorders, independent of their weight loss and metabolic effects.

Emile Andriambeloson

At the press conference, Emile Andriambeloson presented his work testing semaglutide, the active agent in Weygovy and Ozempic, in rat and mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease.

To model Alzheimer’s disease, the rats were injected with amyloid-beta, a molecule that accumulates in clumps in the brains of people with the condition. To replicate chronic brain inflammation associated with Alzheimer’s disease, mice were injected with lipopolysaccharide, a well-known pro-inflammatory agent. Both models developed memory and cognitive deficit as measured by standardized behavioral tests.

The findings show that a week of semaglutide treatment improved memory in the rat model and almost fully ameliorated memory loss in the mouse model.

Further in-vitro experiments suggested that semaglutide may counteract neurodegeneration by reducing brain inflammation: The drug prevented inflammation-induced neuronal death in rat neurons that were co-cultured with supportive glial cells.

“While these findings are preliminary and based on animal models, they pave way for further research into the potential of semaglutide as a therapeutic option for Alzheimer’s disease,” said Andriambeloson, head of research at the French preclinical research company Neurofit. There are now several ongoing clinical trials of semaglutide in Alzheimer’s disease.

Behavior: Exercise and Motivation

Researchers still don’t have a complete picture of how GLP-1 agonists reduce food intake. But interfering with motivation and reward systems is thought to be a key mechanism. This mechanism may also underly early observations that GLP-1 inhibitors seem to reduce the intake of alcohol and drugs of abuse.

Ralph DiLeone

To explore how GLP-1 agonists affect motivation and reward in mice, Ralph DiLeone studies their effects on running — something mice love to do.

The common lab mouse strain DiLeone and his colleagues study typically runs ten to twelve kilometers per night on its wheel. “They run like crazy,” said DiLeone, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Yale University.

The mice are also motivated to access the wheel even if they have to perform an extra task, such as a nose poke, to unlock it. A typical mouse will poke 100 to 200 times to unlock a wheel, even though poking gets progressively harder with each attempt. This system is used to study motivation.

DiLeone and his team asked if semaglutide affected running distance or motivation to run. They found that daily injections of the drug resulted in about a 40% reduction in running distance, and a 25% reduction in how many times mice were willing to nose poke for wheel access. Mice fed a diet that made them obese also showed a reduction in nose poking.

The findings suggest that semaglutide reduces exercise behavior and motivation to access exercise.

Additional experiments are needed in the mice to rule out other reasons for the effects, such as interference with habitual behavior. But if they hold true, the findings will add exercise to a growing list of motivational behaviors potentially affected by GLP-1 agonists.

Meanwhile, there have been no clear data to date suggesting that GLP-1 agonists affect exercise or motivation in people, noted DiLeone, and everyone’s desire to exercise is different. In the future as more people take such drugs for longer periods of time, researchers expect to uncover previously unknown side effects.

Reducing Pain

Yong Ho Kim

Yong Ho Kim and his colleagues have long been intrigued by the ability of food to quell pain, a phenomenon known as ingestion analgesia. Their research led them to ask if GLP-1 could be involved.

Their findings uncover a potentially broad role for GLP-1 in easing pain.

Kim reported that GLP-1 and GLP-1 agonists can attenuate both chronic and acute pain in mouse models. The effects were mediated through a well-known pain sensor in the nervous system called TRPV1.

In the hopes of finding new ways to treat pain, researchers have previously developed compounds that block TRPV1. But such compounds have the side effect of dangerously raising body temperature since TRPV1 is also involved in sensing heat.

That side effect did not occur when mice were treated with GLP-1. Moreover, the researchers found that a more targeted fragment of GLP-1, called exendin 20–29, exhibited highly specific effects on TRPV1 and pain. Exendin 20–29 bound to the extracellular side of TRPV1, effectively blocking its function and alleviating pain in both acute and chronic pain models — all without interfering with GLP-1 receptor function or glucose regulation.

Kim, an assistant professor at Gachon University in South Korea as well as founder and CEO of RudaCure Co. Ltd, is now performing additional experiments on exendin 20–29 and synthetic peptides derived from it.

“This research could lead to the development of novel pain therapeutics in the future,” he said.