Becoming Afraid: How Creepy-Crawlies Turn Creepy

- Published5 Aug 2019

- Author Kerry Benson

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

I don’t recall how my brothers and I captured Thomas the moth, but somehow he ended up at the mercy of three well-intentioned five-year-olds. I have exactly two memories of his existence. In the first, we are lying on our stomachs in our backyard, our mesmerized faces pressed against the wire mesh of his cage. In the second, he is dead.

As we stared at his crumpled, lifeless body, it dawned on us that moths need to eat too. Our revelation came too late for Thomas, but just in time for the other critters that would capture our fascination: first ladybugs, then caterpillars, then (to the horror of our spider-fearing mother) daddy-longlegs. Yet by the time we entered second grade, all three of us were more cautious toward creepy-crawlies, and two of us were afraid.

The stories of three little kids don’t exactly qualify as scientific evidence — but actual research mirrors our experiences with eerie similarity. In 1997, a group of Dutch psychologists asked 129 schoolchildren if spiders freaked them out and, if so, when their fear began. Two-thirds said they had either “some” or “a lot” of fear. And the average age of onset? Six years old. Other research agrees with this estimate, citing average ages of about six or seven.

We aren’t born afraid of skittering insects and slithering snakes. But our brains are hardwired to look at these creatures differently. Couple that with the fact that young brains are impressionable learning machines, and it doesn’t take much to convince us that we should be afraid.

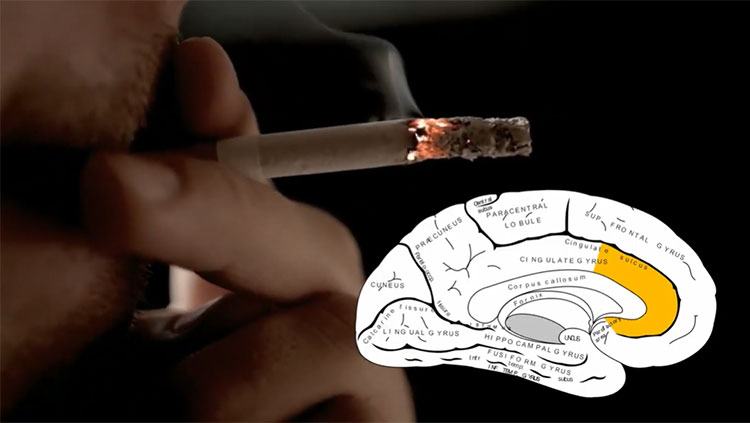

The Neurobiology of Fear

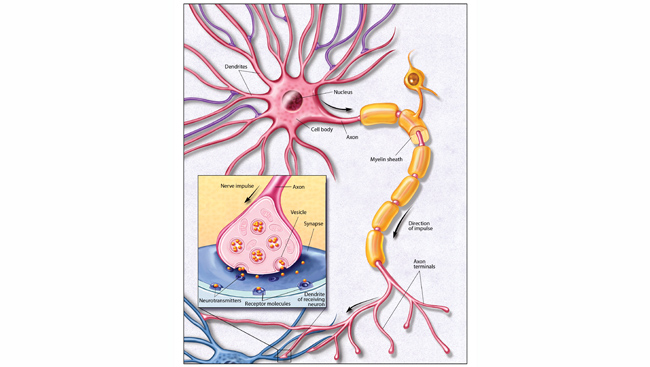

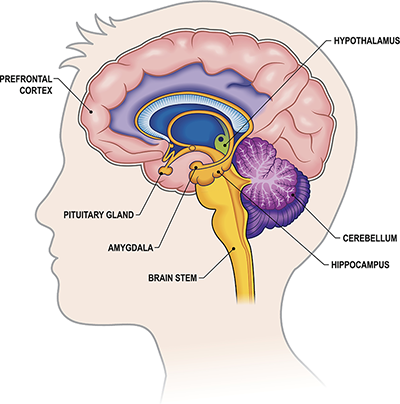

Fear is a two-pronged experience. On the one hand, it’s an innate, physiological reaction to potential threats. Encountering something scary activates the brain’s threat detector, an almond-shaped cluster of neurons called the amygdala. In turn, the amygdala sounds the alarm and triggers the familiar fight-or-flight response, producing a racing heart, dry mouth, and sweaty palms. This all happens automatically, often before you’ve even consciously processed what you’ve just seen.

It’s an “immediate, knee-jerk reaction in order to do whatever you need to do to survive something that’s threatening,” says fear researcher Stephanie Maddox.

At the same time, the amygdala also triggers another, slower reaction that leaves you with that familiar pit in your stomach. This is the second part of the fear experience: a subjective, emotional response. “The combination of all those different, biological hardwired responses” are what we subjectively label as fear, Maddox says. There’s a difference “between just noticing that you have had all of these biological reactions and then putting that subjective label on top.”

Hardwired Vigilance

We may learn to fear creepy-crawlies after a negative firsthand experience, such as a snake bite. But, more often, we learn through observation: by watching others — both the people in our lives and characters in the media — react fearfully to critters.

While all our fears our learned, it turns out some are easier to acquire. In 1990, psychologists Michael Cook and Susan Mineka gathered groups of rhesus monkeys for a horror movie night. The first group watched a film of a fellow monkey reacting fearfully to a snake. The second group enjoyed the horror-comedy version of the film: an edited clip depicting the monkey freaking out over flowers. Apparently, monkey see, monkey do only goes so far. The monkeys watching the first film later displayed fear of snakes, but those that watched the flower clip didn’t acquire a fear of flowers. The monkeys were primed to fear snakes but not flowers.

To determine whether the same is true of humans, Vanessa LoBue has spent many hours of her life attempting to scare babies. In one study, the Rutgers University professor showed eight- to fourteen-month-old infants a series of photographs. By tracking the infants’ eye movements, she found they noticed photographs of snakes more quickly than those of flowers, suggesting the human brain, like the monkey’s, is primed to view these creatures differently. However, the infants didn’t appear afraid of these creatures, because they didn’t cry or show any other evidence of distress. That’s an important distinction, LoBue says, because it confirms we likely possess a natural alertness toward spiders and snakes, which could predispose us to become afraid of them later in life, but we don’t naturally fear them. (She notes even though we’re born with the ability to feel upset, we cannot immediately distinguish between the different “flavors” of negative emotions, like anger and fear. Previous research suggests infants don’t demonstrate fear responses until eight to 12 months of age, which is why LoBue studied older infants.)

Humans may be more likely to pay attention to — and subsequently become averse to — spiders and snakes because of their novelty. They slither and skitter in unusual, unpredictable ways. “Some of us don’t like novelty,” LoBue says. “We tag it as negative.” Even though snakes and spiders aren’t nearly as dangerous as many of us might believe, they can bite. In all, it seems the recipe for creepy-crawly fears calls for three ingredients: a dash of novelty, a pinch of legitimate threat, and several heaping spoonfuls of notoriety.

Vicarious Learning

LoBue believes this last ingredient explains why these fears tend to develop around the ages of six and seven. “Before that, I have found no evidence that children [as a whole] are afraid of snakes and spiders,” she says. “Some of them are, but the idea that it’s widespread — I don’t see much evidence of that in my lab.”

But when we enter the classroom for the first time, many of us learn more than arithmetic. Like those horror-movie-watching monkeys, we often become afraid through vicarious learning. A child who watches her classmates or teacher jump at the sight of spiders may become fearful herself.

Adults can help change that. Parents, she explains, “should be aware that what they say, how they react to different things, what their kids hear in books, on television — that’s going to impact children’s fear beliefs.”

“I’m very wary of my own fear reactions,” she adds, laughing. Last summer, at the beach with her preschool-aged son, Edwin, she glanced down to find an enormous grasshopper on his shirt. “It was about the size of my middle finger,” she says, and even through the phone, I hear the shudder in her voice. For her son’s sake, she suppressed her gut reaction to gasp and banish it immediately. “Instead, I was like, ‘Edwin! Look at your shirt! Look at that interesting grasshopper on your shirt,’” she says. “And then I lightly brushed it off.”

No, you don’t need to grin at the sight of an insect — but if a child is watching, see if you can resist the urge to recoil. For a moment, Edwin’s grasshopper encounter brings me back to my own early memories — back to my unfettered curiosity, back to Thomas the moth as he flitted around that tiny mesh cage. In the end, perhaps their innate sense of wonder doesn’t have to fade. Given proper nourishment, it can thrive and keep its wings.

CONTENTPROVIDEDBY

BrainFacts/SfN

DiscussionQuestions

2. How do we acquire specific fears?

3. Why might snake and spider fears be so common?

References

Cook, M., & Mineka, S. (1990). Selective associations in the observational conditioning of fear in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Animal Behavior Processes, 16(4), 372–389. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2230660

LoBue, V., Kim, E., & Delgado, M. (2019). Fear in Development. In V. LoBue, K. Pérez-Edgar, & K. A. Buss (Eds.), Handbook of Emotional Development (pp. 257–282). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-17332-6_11

LoBue, V., Rakison, D. H., & DeLoache, J. S. (2010). Threat Perception Across the Life Span: Evidence for Multiple Converging Pathways. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(6), 375–379. doi: 10.1177/0963721410388801

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., & Collaris, R. (1997). Common childhood fears and their origins. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(10), 929–937. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00050-8

Öst, L.-G. (1987). Age of onset in different phobias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96(3), 223–229. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.96.3.223