Recognizing the Face of a Murderer

- Published7 Apr 2013

- Author Douglas Fields

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Is it possible to identify a murderer from facial features alone? Supporting evidence comes from a new brain imaging study.

The cherry trees are blooming in Washington, D.C. The splendor of pink petals transforms the Tidal Basin for only a few glorious days each spring, but even for local residents it is easy to miss the fleeting display. I am told that in Buddhism the cherry blossoms represent life itself -- short but beautiful. So I make an effort to appreciate them each spring if I can.

The Metro subway was packed with tourists and like-minded locals this week in route to the Tidal Basin. I spotted an empty a seat next to a middle aged woman perched next to the window. As I approached, she made brief eye contact, then lifted her large gold purse and placed it on the empty portion of the bench seat next to her and extended her legs diagonally like a goalie screening a shot.

Maybe it was my black leather jacket; I don’t know. People make determinations about other people based on nothing but appearances instantly and subconsciously. It is a life-saving marvel of neural circuitry that we are only beginning to understand. At the same time this neural circuitry is the basis for racial profiling and discrimination in social interactions and employment. “Excuse me,” I said as I proceeded to plop down on her gold purse, which she snatched to safety. She did not reply or speak the rest of our ride together as she sat shriveled up next to the window.

From an evolutionary perspective, our brains would not have developed circuitry to form instant subconscious judgments from people’s appearances if it were not biologically useful and important to our survival. Do you think it is possible to identify a murderer, for example, from facial features alone? It sounds a bit like phrenology, but a new study has applied the most advanced imaging method, fMRI, to answer this very question.

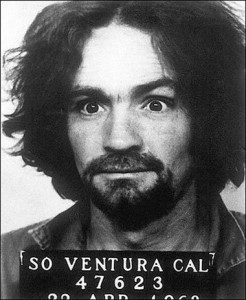

Sixty color photographs of male faces were collected; half of them were images of prisoners convicted of first-degree murder, and half were non-convicts matched with respect to race and age. Then the researchers cropped the images to leave only eyebrows, eyes, nose, and mouth revealed in an ellipse-shaped vignette.

Participants viewed the photos while inside an MRI scanner monitoring regions of neural activity inside their brains. Parts of the brain processing facial recognition and also regions controlling vigilance and fear were activated by the images, as expected. But when the scientists compared the brain responses to seeing the face of convicted murderers to control faces, the nugget of brain tissue well known for emotion, vigilance, and fear, the amygdala, was not more highly activated by the murderers’ faces than controls. Interestingly, when participants were asked to score how threatening each face appeared to them, without knowing whether the image was in fact a murderer or honest citizen, they did judge the murderers’ faces as being significantly more threatening than controls. The test subjects were able to suss out the murderers on appearance alone, even though the photos were tightly cropped to reveal nothing but the parts of the human face that communicate emotion and internal states -- eyes, nose, and mouth.

My explanation would be that murderers do not look different from anyone else, but photos capture the emotions and internal state of a person as conveyed through body language, and the photographs of the convicts were likely taken under circumstances when the prisoners were feeling in a threatening situation, in contrast to when the photos of control subjects were snapped. Still, this reveals the power of our subconscious mind to instantly ascertain a great deal about what is going on inside another person’s mind by a glimpse of their face. The photos were flashed to subjects for only two seconds.

The old idea that specific spots in the brain control specific behaviors or carry out a particular cognitive process is expanding into a new understanding of the importance of networks of communication between brain regions. Rather than looking for hotspots of activity in the brain, such as the amygdala, the researchers wondered if circuits of activity between brain regions might explain how people make instantaneous assessments of others based on appearances. When the researchers sorted their data according to how the participants scored the faces as to how threatening it appeared, with the level of connectivity in neural activity between the amygdala and the part of the cortex involved in facial recognition, a clear pattern emerged in the brain scans. Activity in the amygdala and facial recognition regions of the brain became less well coupled when faces of murderers were presented.

Reduced connectivity between these brain regions makes sense because previous research has associated this with increased vigilance. Reduced functional connectivity between the amygdala and cortical regions is also reported in women with posttraumatic stress disorder, in people with social anxiety disorder, and in mothers with postnatal depression. The reduced connectivity between these regions leads to hypervigilance.

The take-home message is that instant judgments are made by everyone about strangers based on appearances alone and that these subconscious assessments can increase our vigilance to possible threat. I have a clean record, but from this new MRI study I now know that something about my appearance squelched the circuitry between the woman’s amygdala and cortex and prompted her to undertake avoidance behavior. Alternatively, these connections in this woman’s brain may have already been biased toward hyperviligance, either through genetics or past experiences. In that case, any stranger on the Metro would have triggered the same reaction. Considering the importance of experience on brain function, one wonders what an fMRI might show on the way back from the Tidal Basin, after the woman had spent her lunch break strolling beneath the canopy of pink blossoms donated to the United States from the people of Japan as a gift of peace and friendship.

Reference

Miyahara, M., et al., (2013) Functional connectivity between amygdala and facial regions involved in recognition of facial threat. SCAN 8, 181-189.

CONTENTPROVIDEDBY

BrainFacts/SfN