Umami: The Fifth Taste

- Published23 Jan 2019

- Reviewed23 Jan 2019

- Author Jill Neimark

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

More than a century ago, as Kikunae Ikeda savored a simple bowl of broth, he pondered the nature of deliciousness. How was it a lightly simmered mixture of water, dried fish flakes, and a little bit of dried seaweed could be so mouthwatering?

Plenty of food tastes good, but some, like this broth, reach nearly indescribable levels of lusciousness. In essence, Ikeda was asking: is there a flavor for yummy?

Dashi, the broth that set Ikeda on his quest in 1907, maintains an essential place in Japanese cuisine to this day. Ikeda, a chemist, knew the flavor he hoped to isolate would reside in either the fish flakes or the common seaweed known as kombu. Knowing an extract of kombu would contain fewer components, Ikeda chose to focus his efforts on it.

Over the course of a year, he boiled kombu down into a tarry resin and stripped out salts and other organic compounds one by one. In the end, Ikeda harvested a single ounce of crystals redolent of the flavor of his bowl of dashi — a flavor that he called umami, which means savory. The crystals producing that umami turned out to be the amino acid glutamate, one of the basic building blocks of protein. Hoping to provide cooks easy access to umami, Ikeda coaxed glutamate into a form that could be sprinkled on foods and patented it, giving the world the ubiquitous flavor enhancer monosodium glutamate (MSG).

By and large, people around the world have long agreed upon four basic tastes that we can perceive– sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. Each is detected by the taste buds on our tongues and gives us important information about the quality and safety of our food. For example, sweet foods alert us to an abundance of carbohydrate. Bitter foods may warn us of potential poison. That information helps ensure our survival, in part by enhancing the pure pleasure we get from eating and drinking. Ikeda’s discovery of umami teased that perhaps we’re capable of detecting protein in our foods.

“Detecting amino acids in food is really important,” says Gary Beauchamp, of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, “because protein is essential to our survival.”

Many of our favorite foods are chock-full of glutamate: pizza with melted cheese and pepperoni, cooked meat, mushrooms, a bowl of miso soup. As a result, these incredibly popular dishes burst with umami. It stimulates appetite, pleasure, and satisfaction while eating. Glutamate is also abundant in human breast milk; in fact, human milk contains as much glutamate as most savory broths.

Glutamate alone, however, can’t produce the full flavor of umami. Instead, it arises from the combination of glutamate and ribonucleotides, molecules that serve as building blocks for DNA and RNA.

Much like salt, umami serves as a flavor enhancer. People don’t like salt itself, but sprinkled on chips or added to baked goods, salt enhances foods. Umami on its own can be so subtle people don’t recognize it. If you want to know what umami tastes like, chew a tomato thoroughly. You will taste the sweet and tangy flavor, and as you keep chewing, another subtle flavor will become apparent. That is umami, which also reveals itself when you do the same thing with parmesan cheese.

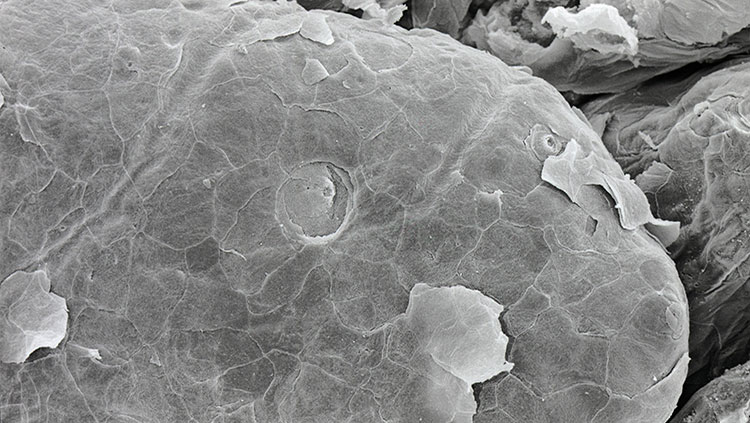

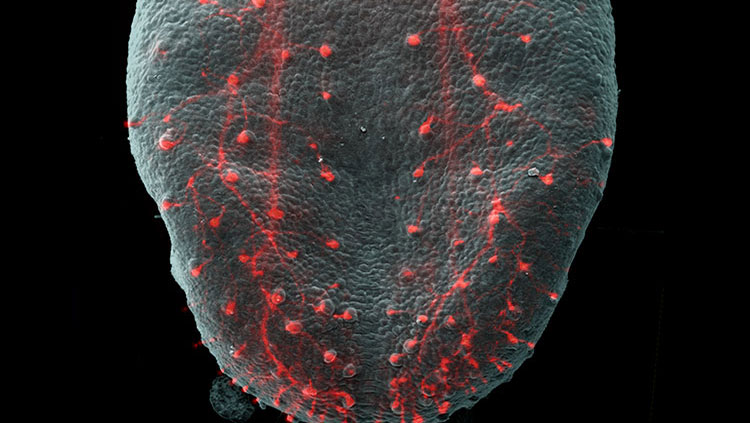

Even though Ikeda identified umami in 1908, it wasn’t until 1985, at the first Umami International Symposium in Hawaii, that the term was officially recognized as the scientific description of the taste of glutamates and nucleotides. Fifteen year later, scientists from the University of Miami identified the first umami receptor on the taste buds lining the surface of our tongues. Several more have been identified since, which isn’t surprising to Monell’s Beauchamp, given the importance of protein in our diets.

The ability to sense umami may play a role in our overall health, says Ole Mouritsen, professor of gastrophysics at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, and author of Umami: Unlocking the Secrets of the Fifth Taste. “Umami stimulates salivation,” he explains. Releasing saliva is an important signal of appetite, just think about how you salivate just when you get a whiff of a favorite food. Saliva is also the first step in digestion, comprised of enzymes that begin the breakdown of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. In addition, says Mouritsen, umami helps giving a feeling of satisfaction, satiety, and fullness.

The secret to developing umami in foods, says Mouritsen, is blending ingredients that offer both glutamate and ribonucleotides. You can find examples of such combinations all over the world. Tomatoes naturally have both, and that may be why ketchup is so popular around the globe, and why pizza and pasta are paired with tomato sauce. Mature cheeses are naturally rich in umami, and anchovies and mushrooms provide nucleotides to boost umami. Fermented foods like soy sauce, or cured meats like bacon and salami are rich in umami. As such, a ham and cheese sandwich, says Mouritsen, “can render an utterly tedious and boring piece of bread not only edible but delicious.”

Umami is truly the taste of “yummy” itself.

CONTENTPROVIDEDBY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Lindemann, B., Ogiwara, Y., Yuzo, N. (2002). The discovery of umami. Chemical Senses. (27)9, 843–844. doi:10.1093/chemse/27.9.843.

Nishimura, T. About Society for Research on Umami Taste. Society for Research on Umami Taste. Retrieved from www.srut.org/about_umami_e.html

Umami – The Delicious Fifth Taste You Need to Master! MolecularRecipes.com. Retrieved from http://www.molecularrecipes.com/molecular-gastronomy/umami/