Understanding the Power of Meditation

- Published19 Apr 2019

- Reviewed19 Apr 2019

- Author Kayt Sukel

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Tibetan monks meditate for hours upon hours each week. Their devotion to their religious traditions makes them experts in the practice of meditation.

Turns out those experts have a lot to teach us about how sustained mindfulness affects the brain.

Meditation and mindfulness induce a heightened state of awareness and focused attention. Various studies demonstrate the practice can help relieve stress — as well as manage anxiety, reduce inflammation, and improve memory and attention, to boot. Such striking results have many doctors, across specialties, prescribing meditation just as they would an anti-depressant or blood pressure medication. But it remains unclear just how meditation confers so many health benefits.

That’s why Bin He, a neuroengineer at Carnegie Mellon University, decided to look at the brains of Tibetan monks. In a previous study, He and colleagues saw that individuals with meditation experience were better able to control a computer cursor with their mind than those without it. Since Tibetan monks spend years of their lives engaged in the practice of meditation, He was curious to see if there might be any significant differences in brain activation that might offer a hint into how meditation leads to so many beneficial effects.

“We went to Tibet and measured activity in the brains of monks who had, on average, 15 years of meditation experience — between five and 35 years,” he said. “We then compared those results to native Tibetans who had never meditated before.”

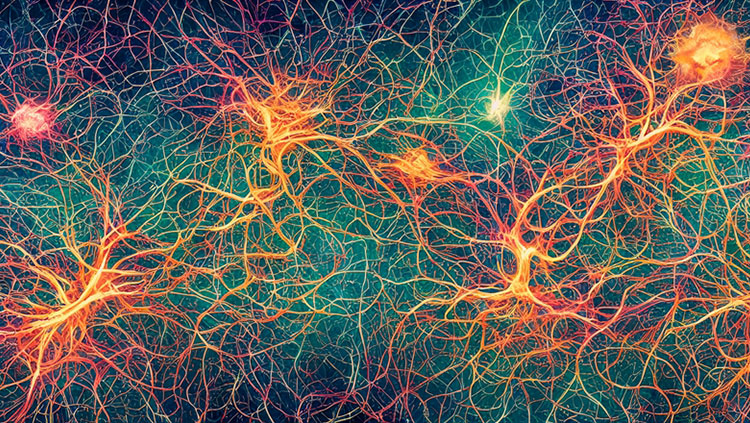

Using electroencephalography (EEG), a series of electrodes placed on the scalp to measure brain activity, He and his colleagues found that long-term, active meditative practice decreases activity in the default network. This is the brain network associated with the brain at rest — just letting your mind wander with no particular goal in mind — and includes brain areas like the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex. What’s more, the longer a monk had been practicing, the bigger the reduction in activity the researchers observed.

“It seems the longer you do meditation, the better your brain will be at self-regulation,” said He. “You don’t have to consume as much energy at rest and you can more easily get yourself into a more relaxed state.”

He suggests that meditative practice helps to “optimize” how the brain uses resources. Pioneering neuropsychologist Michael Posner from the University of Oregon, who first outlined how the brain’s attention systems work, says that makes sense. His own work, with Yi-Yuan Tang, has shown distinct changes to the white matter, or the nerve fibers that allow different brain regions to more efficiently communicate with one another, surrounding the anterior cingulate, a part of the brain heavily involved with managing attention, with meditation practice. Using diffusion tensor imaging, a special kind of neuroimaging technique, Posner and colleagues found increased levels of myelin, sometimes referred to as brain “insulation,” after only a few weeks of regular meditation practice — and that increased insulation helps improve connectivity by letting different brain regions communicate faster and more efficiently.

“This is a major node of attention in the brain — and we can see these changes after only two to four weeks of practice,” he said. “Those changes are linked to improved attention in different tasks. And as the anterior cingulate has vast connections to the limbic system, or emotional system, it helps us understand why meditation can help improve mood and reduce anxiety, too.”

Such results are especially promising considering the participants in Posner’s study didn’t have to join an order of Tibetan monks in order to gain a variety of benefits. Participants improved on tasks measuring attention and problem solving in as little as five days. They also showed reductions in cortisol, a hormone commonly used to measure a person’s stress level, Posner said. Improved cognitive skills and lower stress levels are certainly nothing to sneeze at.

Richard Davidson, founder of the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says he is not surprised that so many neuroscience studies are elucidating the neural mechanisms underlying meditation’s beneficial effects. He says, taken together, there is strong evidence that a regular, consistent meditative practice offers a lot of direct benefits to the brain — and, by extension, to your psychological and emotional well-being. That’s why you shouldn’t be surprised if your primary care provider starts mentioning mindfulness techniques at your next yearly check-up.

With several studies backing up the idea that meditation is beneficial for your brain and body, what kind of practice can offer these advantages if you aren’t able to take up the same kind of regimen as your average Tibetan monk? There’s still a lot of research that needs to be done to understand the type and amount of practice required to get an effect — and it likely will be different for each person. And with so many ways to do so — from workshops to smart phone apps — Davidson says the best kind of meditation is simply the one that you are most likely to stick with.

“Think of it as a form of personal mental hygiene — almost like tooth brushing,” he said. “Humans didn’t evolve brushing their teeth twice a day. It’s a learned skill. Your brain is just as precious as your teeth. So, it’s important to take the time to learn a practice and stick to it.”

This content was created with support from the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at Broad Institute.

CONTENTPROVIDEDBY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Cassady, K., You, A., Doud, A., & He, B. (2014). The impact of mind-body awareness training on the early learning of a brain-computer interface. Technology, 2(3), 254–260. doi:10.1142/S233954781450023X

Jiang, H., He, B., Guo, X., Wang, X., Guo, M., Wang, Z., Xue, T., Li, H., Xu, D., Ye, S., Suman, D., Tong, S., and Cui, D. (2018, November). Brain-Heart Interactions Underlying Traditional Tibetan Buddhist Meditation. Brain Wellness and Aging: Systemic Factors and Brain Function. Symposium conducted at Neuroscience 2018, San Diego, CA.

Posner, M. I., Tang, Y. Y., & Lynch, G. (2014). Mechanisms of white matter change induced by meditation training. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 1220. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01220

Tang, Y.-Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4) 213–225. doi: 10.1038/nrn3916

.jpg)